Ecofeminist: from Resistance to Regeneration

Introduction

To engage with the term «Ecofeminism» is to undertake a radical rereading of the world, one that insists on the profound and systemic entanglement of two seemingly distinct crises: the relentless subjugation of the feminine and the accelerating devastation of the natural world. It emerges not as a mere hyphenation of ecology and feminism, but as a trenchant analytical framework and a lived practice of resistance. At its core, ecofeminism posits that the logic enabling the domination and exploitation of nature springs from the same ideological well as the structures enforcing patriarchal control over women’s bodies, labour, and autonomy. This is not a metaphorical linkage but a material one, rooted in historical processes of colonization and capital accumulation that recast both land and the feminine as passive resources, as inert matter awaiting extraction and utility.

The practices examined in this essay serve as vivid manifestations of this connection. They demonstrate how art and activism become spaces where old narratives can be deconstructed and new ones — narratives of care, interdependence, and partnership — can be embodied. From collective action in the spirit of the Chipko movement to the deeply personal, ritual mergings in the works of Ana Mendieta, Fina Miralles and Mary Beth Edelson, from the symbolic confrontation with agribusiness and finance in Agnes Denes' project to the intimate dialogue with plants in the Planta performance, and finally, to the somatic elegy of Björk’s «Sorrowful Soil», all these works represent different facets of a single whole: the search for a path to healing based on the recognition of the fundamental interconnectedness of all living things.

Ecofeminism and Сommunity

«Chipko Movement» (1973), India

The «Chipko movement», ignited in 1973 in the Himalayan region of Chamoli, stands as a seminal act of non-violent environmental resistance. Its tactic was deceptively simple: where villagers clung to trees to shield them from axes, giving the movement its name — «Chipko» meaning «to hug». While a collective effort, it was galvanized by the decisive mobilization of rural women. Their leadership in defending the forests — a vital source of sustenance — became a catalyst for personal and social transformation, subtly reshaping their own standing within traditional communities. Rapidly spreading across North India, Chipko demonstrated that the most potent ecological defense springs from the deep, lived connection between a community and its environment.

Ecofeminism and Revival

Ana Mendieta — «Imágen de Yágul» (from the Silueta series) (1973)

«Imágen de Yágul» embodies a core ecofeminist principle: the intrinsic connection between the female body and the earth. Mendieta’s performance is a deliberate, physical fusion of the two. She does not simply place her body in the landscape — she becomes an integral part of its cycle of decay and regeneration. The work critiques a patriarchal and colonial worldview that seeks to dominate both women and nature, instead proposing a vision of inseparable unity. By becoming one with the site, she does not portray a victim of death, but enacts a ritual of return and regeneration. The flowers arranged to sprout from her torso are crucial — they visualize life emerging directly from her form, challenging the passive association of womanhood with nature as mere resource. This gesture proposes an alternative vision where the feminine is not exploited but is the active, generative force within the natural world. The work becomes a silent but potent ritual that rejects separation and asserts a profound, cyclical unity.

Ecofeminism and Identity

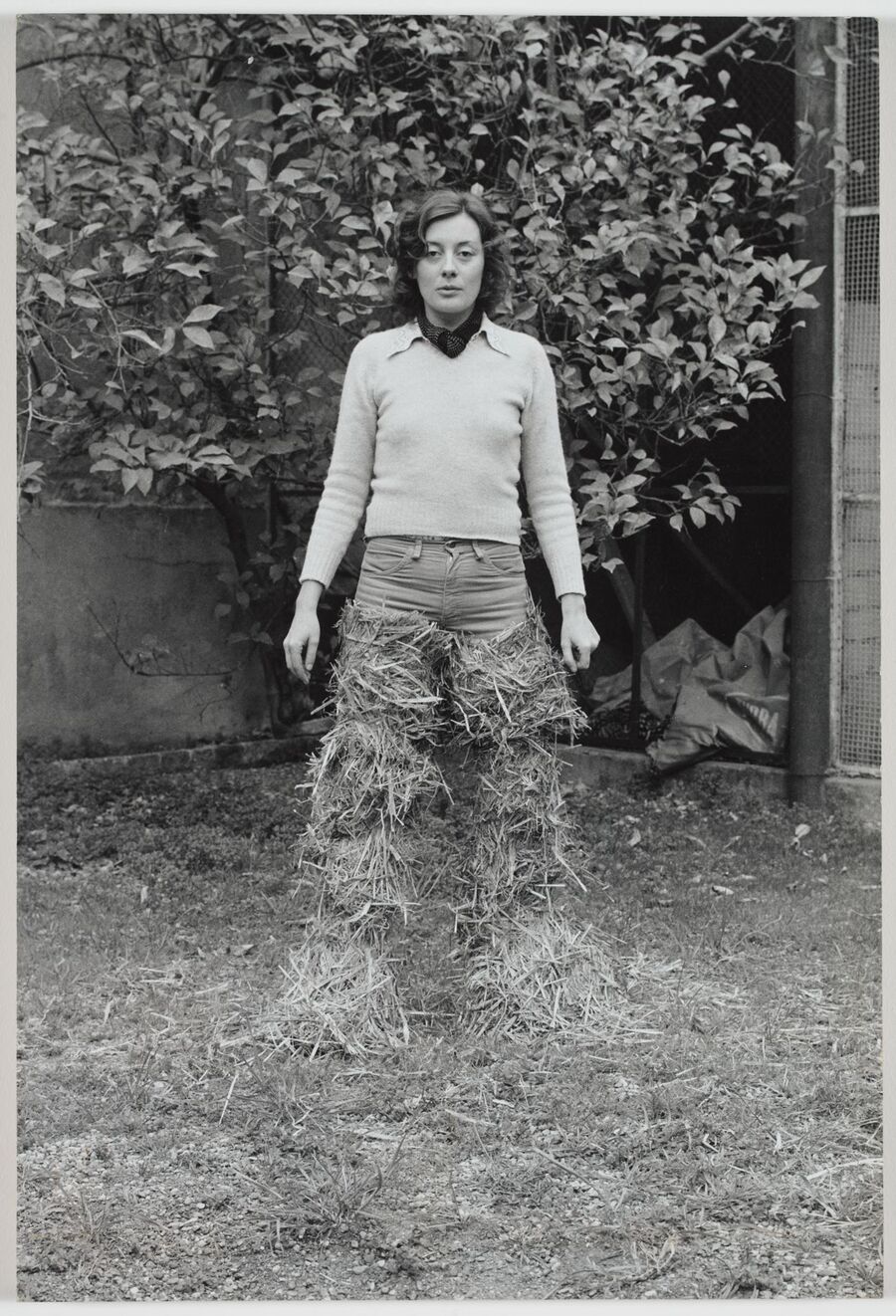

Fina Miralles — «Relations. Relating the Body and Natural Elements. The Body Covered in Straw» (1975)

Eschewing metaphorical representation, Miralles enacts a direct, physical dialogue between the feminine body and the organic world. By completely enveloping herself in straw — a material signifying both agricultural sustenance and ephemeral residue — she executes a deliberate un-becoming. The performance strips away socially inscribed femininity, obscuring individual identity to present the body as an anonymous, terrestrial form. This act of covering is not one of concealment but of transformation: the straw functions not as costume, but as a second skin that assimilates the human into the cycle of growth and decay. Miralles posits the female form not as a passive object upon which nature is projected, but as an active, mutable substance continuous with the environment. In doing so, the work destabilizes the patriarchal gaze that seeks to define and possess both women and land, proposing instead a state of being where identity is dissolved into a quiet, potent symbiosis with the non-human.

Ecofeminism and Female Body

Mary Beth Edelson — «Light Feet» (1977)

Mary Beth Edelson’s «Light Foot» (1977) reconfigures a symbol of patriarchal femininity into an instrument of ecofeminist critique. The chiffon enveloping her form — a fabric culturally coded for lingerie and display — is repurposed. It becomes a permeable membrane that entangles her body with the forest, transforming a sign of confinement into a site of ecological fusion. This quiet intervention subverts the expected spectacle of the eroticized nude. The viewer anticipates an object of visual consumption but encounters instead a subject in active dialogue with nature. Edelson’s performance redirects attention from the body-as-spectacle to the body-as-relation, proposing an identity woven from embodied coexistence. The work’s power lies in this conceptual pivot: it reclaims the female form not by rejecting gendered materials, but by recalibrating their meaning within a framework of interconnection.

Ecofeminism and Financial Capitalism

Agnes Denes — «Wheatfield — A Confrontation» (1982)

Ecofeminist art often transforms the meaning of a place through direct action. Agnes Denes' «Wheatfield — A Confrontation» (1982) is a prime example. The artist cultivated a two-acre wheat field on a landfill in the heart of Manhattan. This project was more than just planting crops. Denes juxtaposed the natural, life-giving cycle of nature (sowing, growth, harvest) with the impersonal financial system, where profit and consumption reign supreme. Her own manual labor became an act of care for the land and a symbol of creation. The golden field against the backdrop of skyscrapers created a powerful contrast. It served as a reminder of what truly matters: food, life, and the planet’s health. Thus, Denes demonstrated that ecological care is not a peripheral concern, but a bold and essential act that challenges the very core of the modern economic system.

Ecofeminism and Partnership

«Planta Performance» (Love At First Sight Festival) (2019)

Planta’s performance is a clear example of ecofeminism in action. It focuses on breaking down the false separation between humans and nature, which is a core goal of ecofeminist thought. Instead of viewing plants as passive objects, the collective’s ritual creates a space for a direct, emotional connection. They use movement and presence to feel «with» the plants, not just about them. This practice challenges the idea that nature must be controlled or managed from a distance. By promoting a relationship based on mutual care and sensory connection, their work argues that truly protecting the planet requires this kind of intimate, respectful partnership. It shifts the focus from abstract environmentalism to a lived experience of unity, showing how feminist principles of care and interconnection are vital to ecological healing.

Ecofeminism and Maternity

Björk — «Sorrowful Soil» (music video) (2022)

Björk’s clip «Sorrowful Soil» manifests a profound, visceral ecofeminist statement. The work moves beyond mere metaphor, creating a potent conflation of the maternal body and the volcanic landscape. By directly addressing the erupting Fagradalsfjall as a primal, generative force, she frames her mother’s mortality within the cyclical, violent, and creative processes of the Earth itself. Björk’s lament does not position nature as a passive backdrop for human emotion, but rather acknowledges a shared, embodied agency. Her grief becomes geological: the volcano’s raw, transformative power mirrors both the creative force of motherhood and the seismic trauma of loss. Thus, the performance becomes an act of embodied philosophy, reclaiming the narrative of life, death, and regeneration by intertwining personal elegy with planetary processes.

Conclusion

Collectively, these practices chart a path from resistance to regeneration. They show that ecofeminism is not merely a critique but a creative, necessary reimagining of our place in the world. It argues that true healing — for both society and the planet — must be rooted in the recognition of fundamental interconnectedness, replacing a logic of domination with an ethic of care, reciprocity, and embodied partnership. The ultimate project of ecofeminism, as these works reveal, is the mending of the very fractures that define our current crises.