Mona Lisa Travels. II. George Pusenkoff, iconographer

DAVID GALLOWAY

GEORGE PUSENKOFF, ICONOGRAPHER

The tradition of icon-painting can be traced to a variety of pre-Christian sources, including symbolic Egyptian representations of pharaohs and their deities. But for the modern world the icon — etymologically, a «resemblance» — first achieved its distinctive form in Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries. The power of the icon to transcend both the pictorial and the material, engaging in direct emotional discourse with the viewer, is a function of its aura. This, in turn, is dependent on a shared code of values and beliefs. Not only representations of the saints but also photos of sports heroes or movie stars may well exude such an aura for those initiated into the unifying rituals. So, too, can individual artworks that seem to incorporate values transcending both technical dexterity and aesthetic accomplishment.

Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda is the undisputed star of this iconographic repertoire — the most famous, the most frequently reproduced, the most commercially exploited image in the history of art.

Exhibition Simply Virtual, Ludwig Museum in the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, 1998

As the seemingly inexhaustible object of homage and persiflage, chemical analysis, historical theorizing and lyric apostrophizing, the Mona Lisa has fired the imaginations of countless artists since 1506, the year when Leonardo presumably completed the portrait begun three years before. But even as early as 1504, one sees its influence on drawings and paintings (including the famous Lady with the Unicorn) by Raphael, who would have known the unfinished work in his colleague’s studio. The oldest outright forgery of the portrait is dated 1540, while the first analysis of the sitter’s mysterious smile was written in 1550 by Giorgio Vasari. And more than 50 copies from the 16th century have been identified. Hence, there is scant substance to the recurrent argument that the source of the painting’s popularity was its highly publicized theft from the Louvre in 1911.

Exhibition Simply Virtual, Ludwig Museum in the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, 1998

Nonetheless, the «kidnapping» by an immigrant Italian workman undoubtedly enhanced the picture’s legendary status, contributing to the appeal it held for early modernists like Malevich and Duchamp. On the day the work was installed again in the Louvre in 1914, more than 100,000 visitors stormed the Salon Carré for a brief glimpse of the homecoming queen.

In the decades that followed, La Gioconda became a recurrent presence on the international art scene, as Marc Shceps details in the following essay on Mona Lisa in the Art of the 20th Century. Of all the artists on whom the lady has cast her enigmatic spell, none has responded with such an extensive and complex body of work as George Pusenkoff. Mona Lisa’s face has provided him with a matrix from which entire environments have been constructed. Pusenkoff has journeyed throughout his native Russia with a black-and-yellow reprise on the Italian beauty, sent her into space, erected a rainbow-hued tower in her name, situated her image throughout Venice from the train station to the Giardini, and even propelled her into the invisible miniuniverse of Nano technology. In a broader sense, he has lent this ageless icon an identity tailored to the 21st century, and he has done so with the aid of state-of-the-art digital tools.

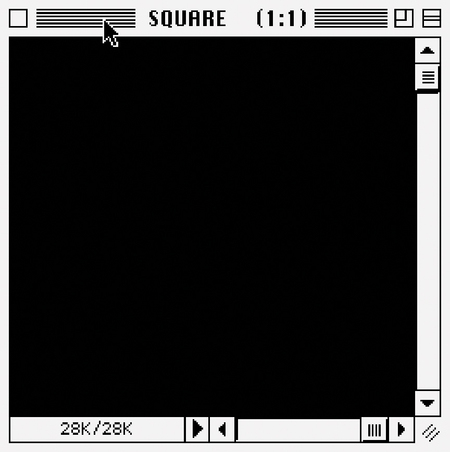

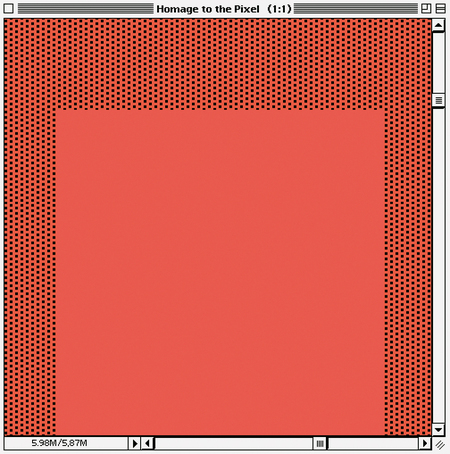

Left: Black Square, 1996. Acrylic on canvas, 70×70 cm Right: Homage to the Pixel (red), 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 210×210×8 cm

Nor is she the only fine-arts icon to have been submitted to Pusenkoff’s digital alchemy. He has also applied it to works by Malevich and Mondrian, Van Gogh and Albers, Rothko and Picasso, among a score of others who created images with an unmistakable auratic power that firmly embeds them in a shared visual vocabulary. Furthermore, each is passed through the filter of George Pusenkoff’s own unique style, starting with the downloading of images from Internet sites, their digital manipulation and lush coloring. In most of these works, the computer task-frame remains visible. In a black-and-gold reprise of a detail from Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, the words «Revert» and «Cancel» are included in computer script within the image itself. Like Warhol before him, Pusenkoff thus calls our attention to the process through which the finished work has passed, as well as suggesting a new kind of image-control that the viewer enjoys. Unlike Warhol, who claimed (perhaps ingenuously) that others often selected his images, Pusenkoff is a connoisseur whose selections are deliberate and informed. His oeuvre represents an ongoing dialogue with art history itself, mediated by the iconic images that mark its progression.

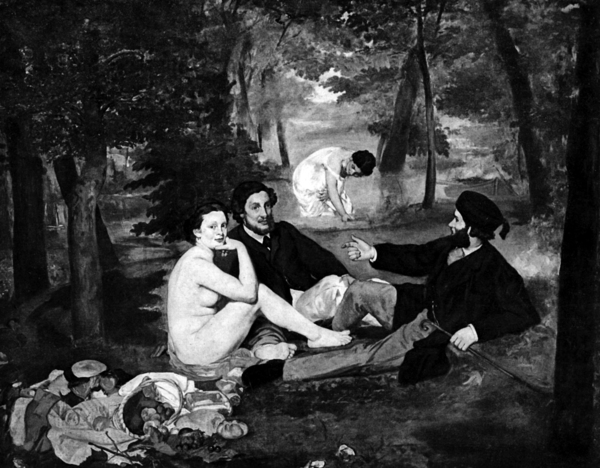

Left: Titian Vecellio, Venus with a Mirrow, 1552–1555. Right: Édouard Manet, Dejeuner sur l’herbe, 1862 –1863. Musée d' Orsay, Paris

When an interviewer asked Mike Bidlo, the master of all appropriationists, what motivated him to choose certain images rather than others, he replied: «The image’s iconicity».

The precision of Bidlo’s painterly impersonations — of Picasso, for example, but also of Yves Klein and Jackson Pollock — raise age-old issues about originality and authenticity, as illustrated by the ongoing problem of Rembrandt attributions. (More recently, even Pollock and Warhol have joined this art-historical free-for-all.) Bidlo’s uncannily accurate reprises also point to a far more important phenomenon that emerged in the last century and found an inventive spokesman in George Pusenkoff: the elevation of classic and/or popular works of art to the status of icons. That process of «sanctification», affecting works as divergent as Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Barnett Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue, was only one indicator that the visual arts were helping to fill a spiritual vacuum in postmodern society. During the building boom that followed World War II and assumed increasing momentum as the century drew to a close, the museum was often referred to as the «cathedral» of the 20th century.

Le déjeuner sur l’herbe & La condition humaine, 2006. Acrylic on canvas. 120×140 cm

Indeed, as church attendance dwindled throughout the West, museum attendance regularly set new records. In addition, a proliferation of art fairs, biennials and international extravaganzas like Kassel’s trendsetting documenta revived the tradition of the pilgrimage.

Left: Manet, Dance, 1991. Acrylic on canvas, 140×140 cm Right: Veronese, Emancipation, 1992. Acrylic on canvas, 110×180 cm

Green Bronzino, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 200×120×8 cm

Like the early, formulaic portraits of philosophers and rulers, deities and saints, iconic works fulfill a cultic function directly dependent on their familiarity to a broader audience. Hence, such images were originally produced according to strict rules of composition, and they were frequently carried in processions or copied to be hung in administrative offices or places of worship in order to broaden their populist base. Whether secular or religious, the objective of such depictions was to inspire awe and devotion, but this reaction depended upon reliable recognition of the subject. According to legends of the saints, a painter accompanied the Magi on their journey to Bethlehem: a significant guarantee that later, stylized portraits of Casper, Melchior and Balthazar were indeed «authentic». In inverse relationship to Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura as a product of uniqueness and individuality, the aura of an icon depends on its capacity for replication, while its authorship is frequently anonymous.

Indeed, it might be argued that it is precisely Benjamin’s «age of mechanical reproduction» which has raised numerous artworks to iconic status by making them part of a common visual heritage. Far more people know Picasso’s Guernica through printed sources than through a pilgrimage to Madrid. Nonetheless, essential questions remain unanswered: Does the reproduction not merely propagate but also «borrow» (and perhaps enhance) the auratic power of the original? If this is indeed the case, from what sources — historical, aesthetic, anecdotal — does that power derive? Why do some images demonstrate this «it» quality and others not? Why do Andy Warhol’s portraits of Marilyn Monroe seem iconic, while those of Elizabeth Taylor lack that dimension? Is it because we supply the subject with information and endow it with pathos imported from the star’s biography? (Might we, indeed, speak of a latter-day hagiography?) Or does Warhol’s silk-screened image itself «borrow» the auratic power of the original photographic source, which in turn captures some of the fragile radiance of a woman with the uncanny power to seduce the camera? And where does that leave the cheeky plagiarism represented by Sturtevant’s Warhol Diptych (1973) or the Richard Pettibone series entitled Andy Warhol Marilyn (1973).

However one appraises the intention and reception of such aesthetic recycling, the fact remains that the aura of the «original» (a tricky concept in Warhol’s case, to be sure) is undiminished. And where is the original that informs Warhol’s various studies of the Mona Lisa? After all, the artist had his photomechanical silk-screens produced from an illustration of the masterpiece, and he isolated the figure from its background to create a new «original». This, in turn, was replicated and combined to form works like Thirty Mona Lisas and the four-panel composition that Richard Pettibone exactingly replicat- ed in Andy Warhol Mona Lisa. In this labyrinth of reproductions, borrowings, imitations and copies of copies, all questions of «source» or «originality» become irrelevant. We are dealing here with an iconic process that undergoes a continuous renewal and is not vitiated but enhanced by repetition.

In the studio, Cologne, 2001

Such resilience is nowhere better demonstrated than in the seemingly ubiquitous image of La Gioconda. Her likeness dangles from key rings like a religious amulet, graces coffee-mugs and lends consumer-appeal to a seemingly inexhaustible range of products from face powder to sanitary pads. Nor is there an end in sight to speculations about the painting’s sitter. Does her smile reflect some secret she is protecting? Is she pregnant? Is she concealing bad teeth? Is she really a boy in woman’s clothing — perhaps even Leonardo’s lover? Is her face that of the painter himself? The latest addition to the Mona monographs, entitled Au cœur de La Joconde: Léonard de Vinci décodé, was published in 2006. It summarizes the results of elaborate analyses of the painting’s material properties, compiled and commentated by 39 scholars and scientists from three countries working at France’s official Center for Research and Restoration. It seems safe to presume that no painting in history was ever submitted to such painstaking, state-of-the-art analysis. One is reminded of E. E. Cummings' ode to «sweet spontaneous earth», which asks: …how often have the doting fingers of prurient philosophers pinched and poked

thee, has the naughty thumb of science prodded thy beauty

In Cummings’ vision, earth answers her insistent questioners «only with spring». Mona Lisa answers her inquisitors with her eternal, enigmatic smile. The riddle, in short, cannot be solved.

Left: Vincent van Gogh, Bateaux sur la rive, 1888. Van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam. Center: The Return of the Hunters, 1997. Acrylic on canvas. Right: Boots of St. Marie, 1997. Acrylic on canvas

With individual works, pictorial cycles, happenings, photographs, sculptures and installations, George Pusenkoff returns the Mona Lisa to its fine-arts context. Without encroaching on the dignity of the original, he passes the image through the distinctive filter of his own aesthetic. This process starts with the downloading of the image from the Louvre’s Internet site and its subsequent cropping. With respect to the actual detail chosen, it is instructive to compare Pusenkoff with Warhol, who isolated a rectangular vertical detail reminiscent of the painting as a whole. It shows the sitter’s hair and her décolleté, as well as the horizontal line of the landscape behind her — in short, a traditional portrait format favored by Renaissance portraitists. (There is also a Warhol version in which the sitter’s hands are visible, but the artist tended to favor the abbreviated form).

Exhibition Square, Museum Ritter, Waldenbuch, 2006

Left: Strong Feeling, 1994. Acrylic on canvas, 200×300×8 cm Center: Homage to Albers, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 120×120 cm Right: Green Mondrian, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 120×120×8 cm

Pusenkoff’s format is square, and it isolates the head of the sitter, cropping it at the top of the forehead, so that the face fills almost the entire picture plane. Since there is no hint of costume or of background, the image undergoes a process of abstraction. It thus becomes «timeless», though at the same time the pixel structure roots the composition in the digital age. Thanks to the integration of a computer frame, that process goes a significant step further. With the aid of this device, Pusenkoff once remarked, «I integrated it into the landscape of the new computer reality. It was not just that the Mona Lisa was located within this frame; the frame also became part of the Mona Lisa. In this way, the Mona Lisa became a computer icon».

Installation Erased Malevich and the Black Square, Kulturgeschichtliches Museum, Felix-Nussbaum-Haus, Osnabrück, 2002

Two further points should be noted here. First of all, the framing of Leonardo’s masterpiece has been a recurrent source of debate among curators and conservationists, and that controversy also tells us something about the picture’s reception. Ours is no exception: with whatever means were available, every epoch apparently sought to make the picture «its own».

The first known frame, described in 1625, was a relatively simple one of carved wood; there were presumably other, unrecorded variations on the taste of the day, before a gilded version in Empire style was fitted in 1809, followed by one in the manner of Louis-Philippe.

Only in 1906 did La Gioconda acquire an authentic Renaissance frame, donated by a noble admirer. Since the dimensions were not perfect, the poplar panel on which the work was painted had to be laterally trimmed: an unthinkable intervention for later schools of conservation. The next crucial decision for the presentation and protection of the work was to place it beneath a pane of glass — a decision that almost cost the world one of its greatest treasures. Among the workmen charged with mounting glass over this and other more fragile masterpieces in the Louvre was Vincenzo Peruggia, the Italian laborer who stole the work in 1911 under the misguided belief it had been illegally removed from his native Italy.

Left: The last futuristic exhibition 0.10, St. Petersburg, 1915 Center: Twice Erased Drawing De Kooning, 1997. Acrylic on canvas Right: Who Is Afraid, 1997. Acrylic on canvas

In connection with Pusenkoff’s own computer frame, which — unlike the shifting vogues of framing as an aspect of decoration — literally becomes part of the picture, there is a significant antecedent in the evolution of the traditional icon.

This consisted in the post-iconoclastic technique of painting the frame as well as the image it surrounded. (Often the two were part of a single piece of wood, whose center had been hollowed out.) Names of the saints and deities or of the historic events being commemorated were complemented by a variety of decorative elements. The frame was thus no longer neutral but an essential element of an overall composition — as it is in the case of Pusenkoff’s refiguring of art-historical classics. The technique he has evolved for applying paint in a succession of dense layers also has parallels in the ancient process of layering lime, linen, thin coats of gesso, then encaustic or tempera and, finally, gold-leaf. Pusenkoff discusses his own surprisingly complex technique in the following interview with Christoph Schulz. Unlike Warhol’s procedure, Pusenkoff’s does not tolerate felix culpa; nor can it be executed by assistants and friends. There nonetheless remains a further vital affinity between the two artists. Like Warhol before him, Pusenkoff is a brilliant colorist. His compositions seem literally saturated with color, which itself takes on a tactile presence. When planning his 20-foot Mona Lisa Time Tower, the Russian artist realized that no existing color-chart would assure him the full spectrum of colors he envisioned for the work. He thus set about creating his own colors, which were subsequently patented.

Installation Mona Lisa Ring, 2005, Manege, 1st Moscow Fine Art Fair, 2005

The circular Mona Lisa Time Tower is constructed of 500 reflecting panels of enamel on aluminum, which means that individual images and colors may well be mirrored in their neighbors across the way. What results is an extraordinary kaleidoscope with the viewer at the center, himself often reflected in the surrounding walls. Furthermore, since the tower is open at the top, the movement of clouds also becomes part of this shifting drama. As though touched by the magician’s wand, the Mona Lisa radiates a vitality and presence that seem to distill the essence of the original, even while they document the remarkable gifts of their contemporary interpreter.