Mona Lisa Travels. IV. Smile please! A Conversation With George Pusenkoff

CHRISTOPH SCHULZ

SMILE PLEASE!

A Conversation With George Pusenkoff

So it’s a smile then that moves across the countenance of the Mona Lisa. But only a very faint smile; it sits in the corners of the mouth, and almost imperceptibly the features alter like a breath of wind that grazes the water, something moving across the soft surfaces of the face. An interplay of light and shadow comes about, a whispering dialogue that one never tires of listening to.

Heinrich Wölfflin

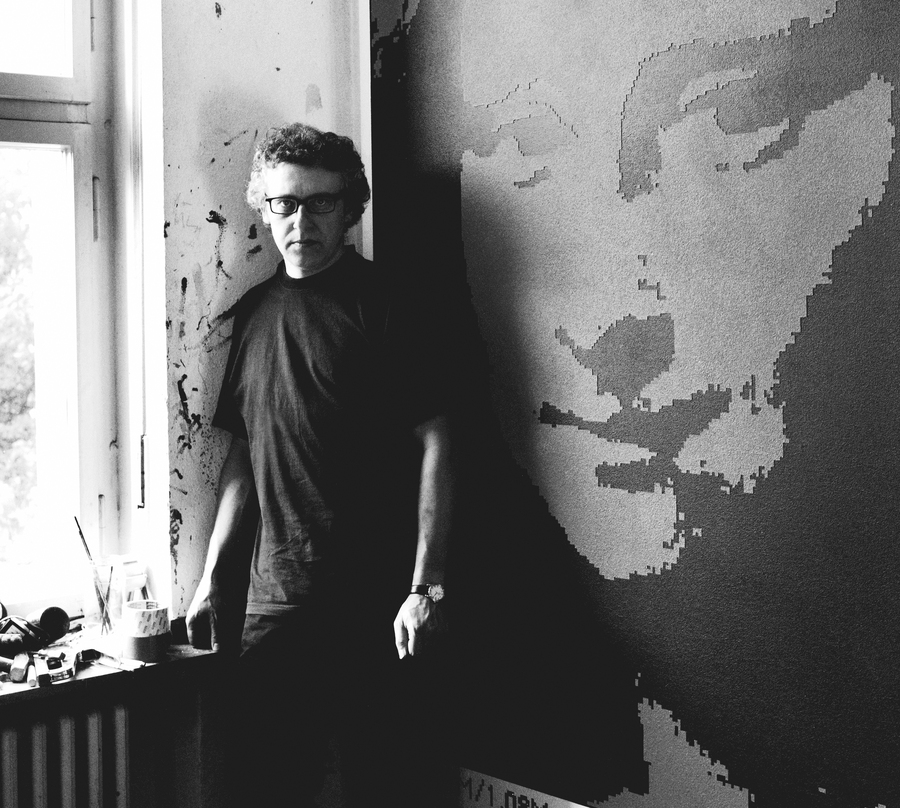

In the studio, Cologne, 1998

HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL

Schulz: A large part of your work consists of pictures about pictures, pictures with pictures — or of pictures. Yet one motif has played a particularly central role since the beginning of the 1990s — one to which this book is dedicated: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. After the Mona Lisa had been seen for a few months in the United States in 1963, as the result of an agreement between the American president John F. Kennedy and the French government, it went on another journey in 1974, this time in a different direction — first to Tokyo, then to Moscow, where it was exhibited in the Pushkin Museum. Can you recall the circumstances that brought about this unusual journey?

Pusenkoff: It was clearly a political gesture. At this time Russia had signaled efforts pointing toward more freedom and democracy. In this context, an agreement was signed between the Russian government and the Americans in which, among other things, it was agreed there would be no further underground tests of atomic bombs. The loan of the Mona Lisa was of course not a direct part of a comparable political agreement with the French, but there was certainly an implicit connection between the two events. In Russia, politics was always closely bound up with culture.

The Mona Lisa thus came to Moscow on June 14th, was exhibited for 45 days in the Pushkin Museum and was taken down again on July 29th.

Every step was accompanied by an official act, speeches were held, people applauded. One knew the press would report throughout the entire world that the most important painting in the history of Western art was being exhibited in Moscow — as a matter of course and without risk. This was a demonstration of Russian normality. The message to the West was clear: If we like, we can also play your little democratic games.

The visitors cue in front of the State Pushkin Museum in Moscow during the exhibition Mona Lisa in Moscow, 1974

Schulz: What memory do you have of this event? Is there anything personal you connect with it?

Pusenkoff: I of course visited the Mona Lisa at that time. For me, as a young Russian artist who could not simply travel to France to see the Mona Lisa there, this was an important event. Every day a new line formed before the Pushkin Museum. Every visitor could look at the picture for exactly nine seconds. The procedure reminded me very much of the visit to Lenin’s mausoleum, where I went as a child with my parents: One stood in line, was swallowed up by the building, hustled past the body lying in state and excreted from the building at another location. The ritual was quite comparable, only that the dramaturgy of the Pushkin Museum was friendlier. But here, too, there was only a single exhibit.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: In front of the State Pushkin Museum, 2001, Moscow. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Schulz: How did the Russian artistic community and in particular the Moscow art scene react to the visit of the Mona Lisa?

Pusenkoff: The whole thing was indeed more like a visit, an event, than an exhibition, and a group of non-conformist artists took this as an occasion to stage an independent exhibition, which of course was promptly forbidden. Thereupon, those in charge modified their plan in such a way that theoretically there was no longer a reason to forbid their request: They wanted to show their pictures on a fallow field under the open sky. Thereupon, the civilian police and the KGB moved in with bulldozers and on this off all days, the 2nd of September, the open space was to be planted with small seedlings.

Then began the battle between the pictures and the bulldozers — a central occurrence for Russian art that is documented in many books.

Left: Bulldozer exhibition, Moscow, 1974.

Right: Moscow, the Red Square 1974

Schulz: Was there a specific reception of the Mona Lisa that was perhaps different from that in West European art — particularly in Russian art of the 20th century?

Pusenkoff: The picture was known, of course, but the whole history attached to the picture, particularly in the 20th century, was completely unknown. At the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, the social transformation of life in Russia began, and with it there also came an extensive and consequential politicizing of art. Dialogue with the West was strictly forbidden. Artists were trapped in a sort of vacuum and had no idea how to orientate themselves. From this point on there was in essence no more contemporary art in Russia. With only slight exaggeration one could say that as a result, the absence of external influences made most artists into socialist artists, for there was no other orientation than that of Russian «reality». What was missing was the knowledge required to take part as a contemporary artist in an up-to-date international discourse. Sotz Art became the only non-conformist alternative. But it was also a reflection of and reaction to Socialist Realism. For me it is Pop Art with a satirical look at Socialist Realism and social reality in Russia.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: Orechovo-Zuevo. Bus Stop, 2001.

L-Print, 120×150 cm (detail)

Schulz: What about the small collage from Malevich in which the Mona Lisa appears?

Pusenkoff: That Malevich took up and made a theme of the Mona Lisa as an art icon as early as 1914 — that is to say, even before Duchamp with his L.H.O.O.Q — was truly an interesting and exciting discovery. Both works are ironic commentaries. Beneath the Mona Lisa on Malevich’s collage a scrap of newspaper is attached with the words «Apartment for rent!» In a figurative sense, this means that the place of the Mona Lisa has become free, that one can occupy it anew.

On one of the Russian journeys in conjunction with the action Mona Lisa Goes Russia, I found private rental notices posted on street-lanterns. I placed my Single Mona Lisa 1:1 alongside and photographed them. That was an homage to Malevich.

Schulz: If the socialistic transformation of life also meant that the Russian avant-garde disappeared from the scene, where did you get your knowledge of Malevich?

Pusenkoff: One couldn’t completely suppress him. Knowledge of his pictures and his artistic position circulated in the form of anecdotes, and before the revolution his works were also printed and published. And if one had contact to a museum, for example to a curator, with a little luck one might get into the storage through the rear entrance of the museum.

Exhibition at the Richard Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, 1989

Schulz: In 1978 there was an exhibition in Duisburg’s Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum with the title Mona Lisa in the 20th Century, which showed that in the 1960s and ‘70s the Mona Lisa was an extremely cherished motif in the visual arts, political graphics, caricature and even advertising. Interestingly enough, other than Malevich no other Russian artist was represented there. Was this because the Mona Lisa was of no interest at this time for Russian art or because here in the West one didn’t know enough about the current Russian scene?

Pusenkoff: The art scene was split into conformists and dissidents, whereby the latter naturally constituted the considerably smaller group. At this point in time the Mona Lisa was not of topical interest to the one or the other. She was neither friend nor enemy, she was simply there. She was an important picture in an important museum and to that extent for both sides an unquestioned constant in art history, but one which played no particular role at that time — or only when it was exhibited in Moscow as a political event.

Left: In the courtyard of the artist’s studio, Moscow, 1986.

Right: Exhibition during the Rock-Art-Parade ASSA, Moscow, 1987

Schulz: If it was not a theme in art, was it perhaps present in everyday Russian life, in the consciousness of the people, precisely in its function as «picture of pictures»?

Pusenkoff: In the sense demonstrated by the exhibition in Duisburg, there was no popular culture that wasn’t traditional or shaped by Socialist Realism, and there was also no advertising in the Western sense. Propaganda had taken over the field and in terms of design exerted its influence all the way to the smallest details of life.

Schulz: How did the Western art world appear to a Russian artist in the 1970s who lived in a country of incredible cultural richness but who had no access to a major part of the art history of the West?

Pusenkoff: In the mid-1970s I studied physics, mathematics and computer sciences. Until the start of these studies I perceived myself as a born artist. Even as a child I experimented artistically — or better: played. My first teacher was the brother of my grandmother, he had studied with Chagall. He was very important for me, since I grew up in a very small village in a thinly populated area of Belorussia where far and wide, other than a village library, there were no cultural institutions and no museums.

After school I once visited a state art academy but quickly observed that this was not the right thing for me, since I didn’t want instruction in Socialist Realism. I then made a 180-degree turn and started my studies in computer sciences because I was sure that even without a corresponding course of study, I would be an artist.

Schulz: What access did you have as an artist to scientific, technical studies?

Pusenkoff: I had the luck to study at one of the most privileged institutions of higher learning in Russia — at an institute for electrical engineering that had just opened and was the Russian answer to Silicon Valley. The institute was excellently equipped. We had outstanding professors and, in addition, the first computers. I studied there for six years and completed my degree. At the time I thought this would be my future, though I secretly spent more time painting than working for the university. At some point or other my professor had taken me aside and confronted me with the consequences of a scientific career. With the decision for such a professional career I would have committed myself to being a secret person and also accepted that I would never be able to travel abroad. For others such a job would have been a dream, but I wanted to be an artist and I wanted to travel.

Single Mona Lisa in front of the monument «Worker and the Kolkhoz Woman», Moscow: 2001. L-Print, 120×50 cm (detail)

Schulz: Did you have concrete ideas, plans, or was it more a question of dreams?

Pusenkoff: With the move to an area near Moscow I had at least come into the vicinity of a cultural infrastructure. But that wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to go to Venice, to visit the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum, since those were all phantoms for me. You can’t imagine how I felt when I was in a museum of contemporary art for the first time in 1989. It was the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, during my first journey to the West. At the time, of course, I didn’t foresee that only a few years later my pictures would also be exhibited there. After the visit I sat in the Dom Café, looked at the cathedral and reflected on the fact that I had just been in a museum for contemporary art, while the police calmly stood around on the cathedral square and watched the punks playing football. It was only in this moment that I became conscious of the whole stress that characterized everyday Russian life and that fell away from me at that moment.

Exhibition at the Hans Mayer Gallery, Düsseldorf, 1991

Schulz: It seems that nearly 20 years separated your first rendezvous with the Mona Lisa and her first appearance in your work. Why did it take so long for her to return the visit?

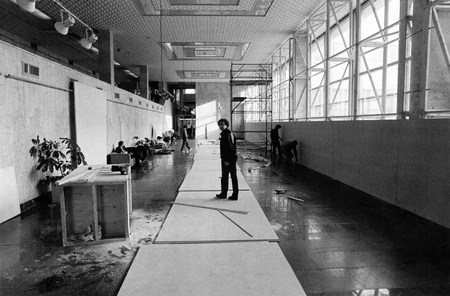

Pusenkoff: In 1993, I was invited to make an exhibition in the Tretjakov Gallery in Moscow. But the architectural situation was terrible. A 40-meter-long canal, a passageway with windows running the entire length. It seemed to me impossible to do something there. And then came the idea of simply building something in front of these windows, to block the view with my works — or, far more, to replace it with pictures whose components consisted of remembered images and fragments of images. I then had a temporary architecture installed before the windows — a fake wall on which I wanted to hang pictures. The hanging was based on a molecular grid, creating the impression of an even wallpaper pattern. .

And when I had the first overall view, it occurred to me: It’s quite obvious that the Mona Lisa is missing here! This is the way the picture …said Duchamp came about, from a smiling Frank Sinatra, Duchamp’s first statement to the readymade and the Mona Lisa.

Actually, the picture was thus created for a very special place on this wall and became a key work for the entire installation

Exhibition The Wall, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1993

Schulz: In what context does pictorial quotation stand in this work?

Pusenkoff: I’ve worked for a long time with quotations and borrowings on various levels. With entire images, details from images, or also with quotations of artistic styles. People like it when they see something they know, when something seems familiar to them. That opens doors. And when they have recognized something, then they start to seek differences from that which they already know.

Schulz: If one looks at your artistic development after this time, one can observe that the quotation as a component of the pictures is replaced by the pixel, from which your later pictures are constructed. When did you discover the pixel as a pictorial point in painting?

Pusenkoff: With the pixel I’ve found a painterly building block in which something like Zeitgeist is inherent on the level of the brushstroke, the painterly trace. Modern painting can no longer simply paint things unreflectively as they «are». One arrives at a new form of expression only through reflecting on the means of presentation, on the «how». I sought for a contemporaneousness of these represen- tational means that expresses how we see today.

In Pop Art the dot of the printed image was typical for the painting of the time. I want the viewer to recognize the time from which a picture comes, to sense a strong relationship to the time of its production.

Left: The painting Strong Feeling in Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 1996. Right: Exhibition The Wall, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1993

Schulz: One could attest to a similar «contemporaneousness» in the interface frame that can be seen on almost all of your pictures — even if, strictly speaking, it doesn’t literally frame. What is the significance for your work of this play with the pictorially inherent frame?

Pusenkoff: The application-frame of the software, visible to the viewer of the image on the computer screen, has become part of the total picture. This is the way things appear when we don’t look for them in a book but look, find and retrieve them from the Internet. Even if I call up the picture from the highly serious homepage of the Louvre, I get this frame built around the picture. The frame is thus not an alienation, not a commentary of my own, but part of the picture we have of the picture. That’s also the reason I don’t paint it separately from the face of the Mona Lisa, but simultaneously with the other parts and surfaces of the picture.

TECHNICAL BACKGROUND

Schulz: When did the computer make its way into your everyday artistic life, and what role does it play in your day-to-day work?

Pusenkoff: In my professional life I was already working daily with computers at the university 35 years ago. In those days they were real adding machines that didn’t even have monitors, only punch cards. The technical prerequisites for dealing artistically with such machines were only opened up for me at the end of the 1980s with the personal computer. For the first time one could also work privately with the computer, at home or in the atelier. I bought my first PC in 1989 for what amounted at the time to the utopian price of 13,000 German marks, and there was only a 250-megabite hard disk in it! The possibilities were correspondingly limited, since even if I only wanted to turn an image by 90 degrees, it took a full 20 minutes of computer time. I made some models and designs for installations on the computer at that time, but they were not intended to be autonomous artworks.

In the studio, Cologne, 2004

Schulz: How do you separate the technical tool from the artistic medium in your work with the computer?

Pusenkoff: The computer actually interests me very little as an artistic medium. And yet there are tasks that only the computer can carry out — or at least much faster. My way of dealing with it is thus rather a practical and pragmatic one. From my point of view, the technical equipment should remain invisible and operate only in the background.

I don’t want to be a media artist because I love the encounter with the material, with the picture or a sculpture. This concrete materiality of aesthetic experience plays a great role for me.

Schulz: Even if many of your pictures look at first glance like prints of digital pictures or, rather, of digital data, so far as artistic discipline and craft are concerned, you are a painter. What does the activity of painting, the practice of painting, mean to you?

Pusenkoff: It’s incredibly important for me. If I don’t paint for a couple of days, I get nervous. And if I don’t have time to paint, I at least get a little paint on my hands. That’s enough to calm me down again! When people come to me in the atelier, they often ask if they can buy the carpet. The traces of work seem to exercise a particular fascination for them, and I can understand that very well. When the pictures are finished, they seem very clean, but the actual process of painting requires great effort, and if one looks closely, one frequently discovers traces of the working process on the sides of the stretchers.

Exhibition Simply Virtual, Mannheimer Kunstverein, 1998

Schulz: Can you describe how the pictures are made?

Pusenkoff: I work a little like the Old Masters, with stencils, cartoons and sketches, very systematically. Mistakes are problematical in this kind of painting, since in the end one perceives the overpainted areas in the unevenness of the surface. The pictures are built up in many layers, with one after the other applied to the canvas. This is more meditative than eruptive — more calculated than a spontaneous outpouring of artistic creativity.

Schulz: That reminds me of printing processes in which the image comes about systematically rather than through an artistic gesture.

Pusenkoff: For me the parallels to a printing process are not so important as those to sculpture or to the relief. For me printing means: to repeat an image as quickly as possible, economically, with as little paint as possible, etc. My working process is different and, unfortunately, not at all economical. If I need 20 layers, then I paint them, one after the other.

With the help of masking and of isolating individual details, I form a relief on the canvas and fill the empty parts with paint. In this way layers come about, but no pressure is exerted, above all not in the temporal sense; sometimes several weeks pass between the individual layers!

In the studio, Cologne, 2004

Schulz: And what added aesthetic value does the work acquire in the end because it is after all painted and not printed, as it may seem at first glance?

Pusenkoff: If someone sees that the picture is painted, he or she hopefully sees as well that it is alive. Our society may be highly technological, but I would like to retain the human qualities of craftsmanship and make them visible. The tradition of art as craft is important to me, and I wouldn’t like to bring that to an end with an iconoclastic, seemingly avantgardistic gesture. Nonetheless, art of course needs a connection to the technological reality in which we live, from which our perception is constantly surrounded. Because this level of reality doesn’t hold back before the reality of art. I would like to find pictorial solutions that unite technology and craft. I want to connect new technology with conventional material, but not to make a mechanical picture.

In the studio, Cologne, 1997

Schulz: With respect to painting, would you describe yourself as a purist?

Pusenkoff: Self-limitation, in the sense of concentration on a tradition, is very important for my work. Painting means quiet, contemplation. The result, the picture, is a picture. A picture can’t be more than simply that — and this is also a good thing! The purely formal artistic experiment is for me too little. As a picture, it is perhaps interesting for a moment, but if one doesn’t succeed in creating a context, its effect is quickly exhausted.

I need the historical context of painting as a sparring partner. I can’t suspend the laws of painting every day and invent them again.

What gets shown today as young painting is mainly nothing new; in my opinion, for many years now only a few artists have developed painting further. Today the disciplines are indiscriminately muddled up. Artists make one thing on one day and on the next something completely different. They are less interested in the picture than, at best, the painterly gesture.

MONA LISA ALONE

Schulz: What formal relationship does your Mona Lisa have to the original? Do you see it as parody, as homage, as updating, as radicalizing, as intensification of central aspects of the original?

Pusenkoff: When an old Russian icon-painter paints an icon, he doesn’t paint the picture of a saint but the saint himself in the form of color. What results is an identification between the painting and that which is painted. My picture can say: I am the Mona Lisa. When you see me, you see the Mona Lisa, you remember her. In the memory of the viewers who have seen my picture, what remains is that they have seen the Mona Lisa, not a picture of the Mona Lisa that I have painted.

Like Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, mine is also authentic, since it doesn’t pretend to be his Mona Lisa, yet one recognizes the same face, the same person whom we know — thanks to Leonardo — as Mona Lisa. It is a contemporary portrait of the Mona Lisa, not so much of the historical person as of the picture.

Louvre website with Mona Lisa, 1997

Schulz: As is so often the case in modern portrait painting, an artistic alienation separates the representation from its relationship, its reference.

Pusenkoff: The alienation, as for example the reduction to the three colors yellow, black and white, was a painterly problem. So far as the graphic alienation is concerned, I spent a month making drawings and designs until I had found the right degree of alienation. The picture looks as though the shadowing could be easily achieved with a Photoshop filter, but that is one of the points where the technical possibilities can’t solve the problems of the painter. With Photoshop the composition becomes a dead and lifeless pattern. I tried various things with a pixel brush, created concentrations of pixel modules, placed them in different sizes and as accents on different places on the face. I wanted even the abstraction to breathe and vibrate like the original.

Even if the picture looks like the «original» and one immediately recognizes the Mona Lisa, a lengthy and demanding process of abstraction lies between them, so that on closer scrutiny not much remains of the former. One transposes the idea of the picture, and on this level a certain similarity reemerges.

Schulz: The glance, the eye contact between work and viewer, seems to play a special role for many of your pictures. When figures appear in your works, they almost always look directly at the viewer in an almost provocative way. What does this indicate?

Pusenkoff: What interests me is the short-circuit between picture and viewer. The picture is like an interlocutor to whom one devotes his attention. I believe in a sort of mini-mimicry effect on the part of the viewer after he has discovered himself in the picture and accepts particular offers, like a smile. That’s the reason people respond to the Mona Lisa with a smile. No one returns frustrated after seeing the picture.

MONA LISA GOES RUSSIA

Schulz: At the end of the 1990s you sent the Single Mona Lisa on a journey. Was the picture created for this action, or did the idea for the journey emerge from work on the picture?

Pusenkoff: Actually, the first journey wasn’t planned as a journey, but was more a question of transport. When the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg decided to buy a version of the Mona Lisa, they wanted to have it as quickly as possible. And so I drove the picture from Moscow to St. Petersburg in a minibus. During this trip I had the idea to stop and photograph the picture at different locations. I found the results, the prints, so interesting that the spontaneous idea for the project Mona Lisa Goes Russia emerged. I then traveled through Russia with another version that I made specially for the project.

How many journeys I made and how long I was underway as a whole, I no longer know, but the series consists of 500 photos that were made at 500 different locations.

Mona Lisa Ring, 2005. Aluminum, acrylic lacquer (50 colors), varnish, diameter 10 m, width 60 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Moscow, 2007

Schulz: From your point of view, what is there about art or the reception of art that changes when a work is not shown in a museum but in a public space?

Pusenkoff: So far as this project is concerned, I’ve also shown the picture in museums, alongside Tatlin, Malevich and many others, as well as en route. Astonishingly enough, the museum visitors who saw the picture in the permanent collection alongside established works of the 19th century and of the Russian avant-garde were no less irritated than many passersby on the street. One can’t even say where the people react «better». One might perhaps assume that the visitors to a museum are prepared, would be less irritated and react more positively. But that’s by no means the case.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: In the State Russian Museum with the painting of A. Ivanov «The Manifestation of Christ». St. Petersburg, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Schulz: In the course of the last few years, has the street or the museum proved to be a more suitable or at least more preferred location for an exhibition?

Pusenkoff: What applies to both locations is that art is a balanced, calculated disturbance, and in Russia this sort of disturbance has a particularly explosive force in a public space. In the museum a picture disturbs in a completely different way. It prompts completely different reactions than it does on the street. To be sure, this disturbance occurs only at the beginning. It is a very brief moment in which irritation functions as provocation. And then it first becomes really interesting when it is a question of how this irritation is brought under control socially, how it is defused and what emerges from it.

Photos from the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia

Schulz: How does the exhibition of the Mona Lisa proceed in situ? Do you simply put the picture there and watch what happens, or is there a sort of ritual?

Pusenkoff: It’s always very spontaneous, a little like a performance that one has to plan and carefully realize in the shortest period of time. In the process I’m director and actor all in the same person. I see a location where I think the Mona Lisa would function well. The goal of the action is to make a photo and not merely to arrange a beautiful or poetic moment. I have to balance the Mona Lisa in the surroundings so that the photo on the one hand seems harmonious but, on the other, captures the surprising aspect of the moment. And most of the time the performance is also ended with the photo.

Schulz: How intensive is the contact between you and the passersby during this event? How present are you as an artist?

Pusenkoff: Actually, I’m at work when I set up the picture and first of all probably look merely occupied. But there are nonetheless interesting encounters, and sometimes I speak to passersby and ask to be permitted to photograph them with the picture. As soon as people are involved, the procedure naturally takes longer.

For example, once near Red Square in Moscow I spoke to an orthodox monk at a church. He of course wanted to know why I was making the photo and when I answered, «For art history», he laughed and signaled his agreement.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: Moscow. Red Square, Iversky Gate, 2001

Mind you, I had to make a donation to the church! I then «hung» the picture, but on my way to the camera, it fell over. Again and again! After the third accident the priest took me aside and very confidentially told me, «What do you expect? That’s a completely normal aerodynamic effect that occurs here. Since Manegen Square is very hot and we’re standing here in shadow at the end of the arcades, a strong wind comes about». And as it turned out, he had earlier been a fighter pilot, so he was familiar with aerodynamics.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia. Top left: Moscow. Yauzskij Boulevard, 1998. Top right: Moscow. Street signs, 1998. Bottom left: City of Dresna. Memorial, 2001. Bottom right: Village House, 1998

Schulz: Do you see the picture Single Mona Lisa 1:1 as an individual work or more as an action, perhaps a social sculpture in the sense of Joseph Beuys?

Pusenkoff: Yes, one can see it that way. That’s at least a quite central aspect of Mona Lisa Goes Russia. Mind you, I’d like the photos to go beyond a mere documentation and become independent artistic works, «pictures». The documentary aspect consists primarily in photography as an image-making process. The design of the picture — how could it be otherwise? — is above all a painterly problem!

Village of Emilianovo, 2001

MONA LISA GOES SPACE

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Space: Single Mona Lisa 1:1 at the Cosmodrome Baikonur, 2005

Schulz: With the action Mona Lisa Goes Space, the Russian journey of your Mona Lisa finds a highpoint — not only so far as the concrete physical height of the hanging is concerned, but also with respect to the degree of the spectacular. How did this journey come about, which seems almost more unrealistic than the journey of the original to Moscow?

Pusenkoff: The idea for the project came to me one day as a logical consequence and continuation of the journey through Russia, and from this moment on I was obsessed by it — perhaps because, at least in the beginning, it seemed virtually unrealizable. But that mobilized all my energies and spurred my imagination so far as the implementation was concerned. From the Renaissance until today, thanks to his positive energies and his belief in the realization of the impossible, man has achieved unbelievable things. Unfortunately, in everyday perception his failure plays a far too central role. The action was also a highly personal campaign of revenge against the pessimism that is spreading not least of all because of the increasing cuts in public funding for culture. I wanted to give a positive example, a positive provocation.

What interested me about the project in terms of content was the relationship between science and art. In the Renaissance, both systems were still connected and not differentiated in the way we are accustomed to in our time. This, too, recalls the work of Leonardo Da Vinci. Today, space travel as a science can no longer be art, but one can use its knowledge to create art and in this way to recreate a connection between them both.

Schulz: One imagines that when working in the space agency other interests count than those of aesthetic experience. How did the administration, the technicians and — not least of all — the astronauts react to the plan?

Pusenkoff: First they declared me crazy. The institutions that had to be convinced themselves work like their machines. They have no questions and no answers that function simply. And so at first one didn’t understand at all what I actually wanted, so surprised were those in charge. In the end, they sought to come to terms with me by theoretically wanting to help me but always coming up with new «practical» objections that allegedly spelled failure for the project. That’s a normal bureaucratic strategy! By chance I then got to know a representative of the French authority for space research who called to my attention that an Italian astronaut would also be along on the flight. And so I wrote to the Italian ambassador in Russia. Luckily, he was fascinated by the idea and during our meeting immediately called Roberto Vittori on his mobile phone. After that, even the wheels of the Russian administration turned faster. The problems had far less to do with the practical implementation of the project than with the persuasive power of the management.

To move people to do something that they don’t have to do — that’s the real art!

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Space. Left: Italian Astronaut Roberto Vittori at the ISS in weightlessness, 2005. Right: Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev during eye test, 2004. Courtesy ESA and FSA

Schulz: How did the action proceed once the administrative side had been clarified?

Pusenkoff: A few weeks before the launch I traveled to the take-off location at Star City. I wanted the Mona Lisa to go through all the necessary stations of preparation in an orderly and conscientious way. Those include training units, medical examinations, technical checks, discussions and of course some of the private life in the astronauts’ recreation rooms. For reasons of space, we took the picture from the frame and rolled it up for the journey itself. The astronauts kindly represented me and made the photos. Now the picture is here in the atelier again and the Mona Lisa looks out the window.

MINI MONA LISA

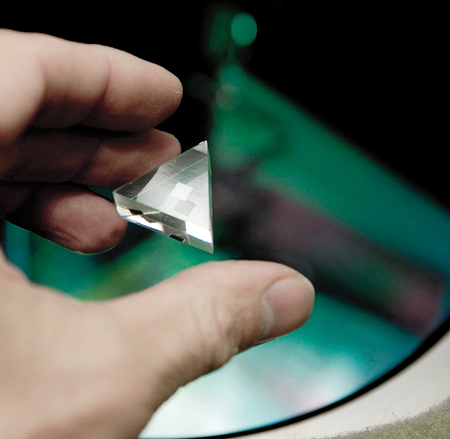

Schulz: Parallel to this large-scale action, the Mona Lisa experienced a shrinking process into the nano dimension. What’s concealed behind nano technology?

Pusenkoff: Basically, nano technology is not a clearly definable technology but a collective term that describes work in a particular physical dimension: the work with individual atoms with a structural size of up to 100 nanometers.

A nanometer is one-millionth of a meter or, expressed differently: to the tenth power minus 9 meters.

Schulz: It sounds as though the project would be easier to realize at the administrative level but no less demanding in its artistic-technical aspect.

Pusenkoff: That’s true. For this project I worked together with friends whom I knew from my student days in Zalenograd and who stayed on there when I went to the West. After many years, at a party I met a friend again who is the director of the largest concern for nano technology in Russia. During the course of this evening we discussed and planned the entire project right down to the last detail. The human chemistry was in order, and beyond that as someone trained in physics I was also a scientist, then a friend, then an artist, and this combination made many things easier.

Mona Lisa represents nano technology at the Russian pavilion at EXPO 2005, Aichi, Japan, Courtesy NT-MDT Moscow, 2005

Schulz: How should one imagine an artwork in nano dimensions?

Pusenkoff: As very small — one could almost say: too small to be an artwork! The actual image of the Mona Lisa is found on a metal plate that measures approximately two by two millimeters and is suspended in a synthetic crystal. On this minute piece of metal there is a tiny point. Within this point, an area is defined that is approximately 1/100th of this point itself, and here there is a relief of the Mona Lisa. To produce this relief, the tip of a needle is electronically charged and with a computer-driven robot guided to the area on which the image should appear. Finally, the oxygen is withdrawn, and everywhere where the tip of the needle has touched the carrier material, it oxidizes. In this way, a relief is created that is built up of molecules.

In theory this doesn’t sound so very complicated, but in practical terms the work can even be disturbed in this dimension by the continental shift.

Schulz: That is something that one indeed can’t imagine, yet at the same time one must imagine it, since one surely can’t see it.

Pusenkoff: The relief is in fact so small that not even light can make it visible. Nano technology works in areas in which the objects are smaller — more precisely, shorter — than light-waves. In these dimensions one can see only with the aid of interpretations. The object is scanned with a computer signal whose findings are translated into an image that we can then see on a screen. The object itself, on the other hand, is quasi invisible.

Left: The transperent prism with a nano chip wearing the image of Mona Lisa, ISS. Courtesy ESA. Right: Image as seen through the electronic microscope, produced in collaboration with NT-MDT. 2005

Schulz: An invisible artwork of course confronts a museum with a great challenge. In what context has the Nano-Mona-Lisa been exhibited?

Pusenkoff: The project was shown for the first time at EXPO 2005 in Aichi, Japan, where Russian nano technology was presented. Apart from this, the Nano-Mona-Lisa can be seen as a permanent exhibition in the space station ISS. The Russian captain Sergei Krikalev took it with him into space. It can be found now in the communal lounge in a small, altar-like situation, alongside a picture of Yuri Gagarin and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky — that is to say, alongside the icons of space travel.

By the way, as luck would have it, the rocket was launched on April 15th. And although the launch as well as my project was meticulously planned, none of those involved were aware of the significance of this date: It was the birthday of Leonardo da Vinci!

MONA LISA — TOUR DE FORCE AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Installation Mona Lisa Goes Venice: Big Mona Lisa. Punto de la Dogana, 2005. Silkscreen on aluminum, 300×300×5 cm

Schulz: In comparison to the action Mona Lisa Goes Space, the tower that you showed for the first time at the Tretjakov Gallery in Moscow, then at the Biennial in Venice, is a mammoth but down-to-earth, earth-bound project. Instead of withdrawing the Mona Lisa from the viewer’s field of vision, you surround him with 500 smiles in all colors of the rainbow.

Pusenkoff: It was, in fact, the greatest project I’ve ever realized. Just as Mona Lisa Goes Space emerged from the previous travels through Russia, this project is connected in terms of content and emotion with the appearance in outer space.

I see the installation as a kind of UFO, a foreign body, that first landed in Moscow, then in Venice, and now here before the Ritter Museum, in the countryside in Waldenbuch!

Schulz: How did the color spectrum come about?

Pusenkoff: I gave considerable thought to the question of how an artistic relationship could be established between the 500 Mona Lisas and their colors. I didn’t want simply to make a colorful pattern, but sought for the most fundamental connection possible. For me as scientist the answer was actually obvious: the color spectrum. The realization, on the other hand, was more complicated than I had imagined. I thought one could simply pick the colors from an RAL chart and the smooth transitions would come about automatically. But with the standard values one doesn’t achieve the fluid transitions and the impression that a color wheel seems to close.

For that one requires a spectrum of 50 precisely structured tones and half-tones that I developed for this work with the RAL Institute. This color sequence has now been patented; every color has its own number, a code, and all of them together are my little secret.

Erecting of Mona Lisa Time Tower in Venice

Schulz: Are you creating a memorial to the Mona Lisa with this work, or is it more a case of enabling the viewer to have a specific experience with this image?

Pusenkoff: Creating a memorial was actually not my intention. And yet de facto it has probably become one, because it is a location where one remembers the Mona Lisa. The function of the memorial is here integrated in the work of art; the artwork fulfills the function of a memorial but is more sweepingly conceived, more ambiguous.

The entrance to the Mona Lisa Time Tower, Piazza St. Lucia, 51st International Art Exhibition / La Biennale di Venezia, 2005

Schulz: What art-historical connections interest you in the form of the rotunda, which from the outside recalls a tower which encloses something — making the Mona Lisa into a kind of fairytale figure — and at the same time recalls the panorama of the 19th century, in which landscapes were usually simulated. The panorama tends to be associated more with the opening of the field of vision.

Pusenkoff: In the case of a work of art, these two versions are not mutually exclusive. From one view- point, it is a panorama, from the other a tower. The installation thus plays with this, making use of the traditions and the associations of both architectonic forms without fulfilling their functions. At first I had imagined a gigantic wall, but the rotunda seemed to me richer in allusions, more eloquent.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Israel: Jerusalem, Temple Mountain, 2007

Schulz: On the one hand, the work shows a panorama of the Mona Lisa, declined through the complete color spectrum, while at the same time the full range of all Mona Lisas can be found here, represented by the individual color values enclosed within this tower. Has your preoccupation with the Mona Lisa in this way achieved its peak, perhaps also its end?

Pusenkoff: Unfortunately — on the other hand, happily we don’t have them all here, but only 500! The number resulted from the fact that the Mona Lisa had just become 500 years old when I started the project in 2002. Whether the installation marks the end of my fascination with the Mona Lisa or not is something I can’t foresee at the moment. I’m happy to be able to show something with this work that is very important to me. As a consequence of having 500 Mona Lisas on the inside, there are 500 black squares on the outside!

The installation is like the famous head of Janus, which has two sides, two faces. And for me that’s what it’s really all about: The Mona Lisa is a black square with a smile.

George Pusenkoff. Single Mona Lisa 1:1, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 70×70 cm

BIOGRAPHY

1953 born in Krasnopolje (USSR) 1968 the family moves to Moscow 1976 graduation from the Moscow Technical University for Informatics, Moscow 1983 graduation from the Moscow Academy for Polygraphic Design, Moscow Since 1983 exhibiting in Moscow and abroad Since 1990 based in Cologne and in Moscow

SOLO EXHIBITIONS (selection)

1989 Richard Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh Hill Gallery, London 1991 Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf 1992 Fernando Quintano Gallery, Bogotá (cat.) 1993 Evelyn Aimis Gallery, Boca-Raton / Toronto; The Wall, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow and Hans Mayer Gallery, Düsseldorf (cat.) 1994 TransArt Exhibitions, Cologne 1995 Ursula-Blickle-Stiftung, Kraichtal (cat.) State Russian Museum, St.Petersburg 1996 Galerie Brigitte March, Stuttgart 1997 Simply Virtual, Mannheim (cat.); Erased Rauschenberg, Galerie Benden & Klimczak, Cologne; Mona Lisa in Russia, Marat Guelman Gallery, Moscow; Galerie Brigitte March, Stuttgart Homage to the Pixel, Cologne (cat.) 1998 Breakfast on the Grass, Galerie Ernst Hilger, Vienna (cat.); Simply Virtual, Museum Ludwig in the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; Digital Expressionism, Galerie Brigitte Schenk, Cologne 1999 Galerie Brigitte March, Stuttgart 2001 Erased Dreams, Galerie Brigitte Schenk, Cologne; Art & Pixel, Espace Ernst Hilger, Paris 2002 Mona Lisa Goes Russia, Heidelberger Kunstverein, Heidelberg (cat.); Erased Malevich, Kulturgeschichtliches Museum; Felix-Nussbaum-Haus, Osnabrück; Painted and Erased, Märkisches Museum, Witten; Museum Korbach, Korbach (cat.); Digital Field Paintings, Galerie Bernhard Knaus, Mannheim; Mona Lisa Goes Russia, Städtische Galerie, Iserlohn 2003 Erased or not Erased, Jüdisches Museum Westfalen, Dorsten (cat.) 2004 Mona Lisa 500, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow 2005 Between Digital and Analog, Sacral and Profane, 1. Biennale of Contemporary Art, New Manege Hall, Moscow Mona Lisa Goes Space, 51. International Art Exhibition / La Biennale di Venezia Galerie Uwe Sacksofsky, Heidelberg 2007 Mona Lisa und das Schwarze Quadrat, Museum Ritter, Waldenbuch 2008 Museum Bochum; Museum of Modern Art, Moscow; pARTner project, Moscow

GROUP SHOWS (selection)

1989 Frühstück im Grünen, Todd Gallery, London 1993 Adresse provisoire pour l’art contemporain russe, Musée de la Poste, Paris (cat.); Junge Kunst 93, Sammlung / Collection Daimler-Benz, Stuttgart (cat.) 1994 Grün beruhigt, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach Europa — Europa, Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn (cat.) 1999 Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf; Espace Ernst Hilger, Paris 2001 Art against Geography, Museum Ludwig in the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg and Guelman Gallery, Moscow (cat.); Nicht Ruhe geben, bis die Erde quadratisch ist, Mannheimer Kunstverein, Mannheim (cat.); Jäger und Sammler, Galerie Brigitte Schenk, Cologne 2002 Warhol Connections, Guelman Gallery and L-Gallery, Moscow (cat.); Abstract Art in Russia, XX Century, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (cat.); Das Rote Haus, Städtische Galerie Villa Zanders, Bergisch Gladbach; Mythos Marilyn, Galerie Ernst Hilger, Vienna (cat.); Kunst nach Kunst, Neues Museum Wesserburg Bremen (cat.) 2003 Life of a Legend, County Hall Gallery, London (cat.); Das Recht des Bildes, Jüdische Perspektiven in der modernen Kunst, Museum Bochum (cat.); Das Quadrat in der Kunst, Sammlung Marli Hoppe-Ritter, Museum Ettlingen; New Countdown — Digital Russia, Guelman Gallery together with SONY, Central House of Artists, Moscow (cat.) 2004 Stella Art Gallery, Moscow. Moskau–Berlin, State Museum of History, Moscow (cat.) 2005 Square, Museum Ritter, Waldenbuch (cat.); EXPO 2005, Russian Pavilion, Aichi, Japan; International Art Exhibition / La Biennale di Venezia; Faces, Guelman Gallery, Central House of Artists, Moscow (cat.); Russian Pop Art, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (cat.) 2006 Der gestohlene Blick, Art Loss, Cologne 2007 I Believe, 2. Biennale of Contemporary Art, Vinzavod, Moscow (cat.)

WORKS IN PUBLIC COLLECTIONS:

Bolschoj-Theater-Museum, Moscow; State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; Museum of Modern Art, Moscow; Foundation of Ministry of Culture, Moscow; MIET (Moscow Technical University); Sammlung DaimlerBenz, Stuttgart; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Museum Ludwig, Koblenz; Ludwig Forum, Aachen; Museum Bochum; Märkisches Museum, Witten; Jüdisches Museum Westfalen, Dorsten; Museum Ritter, Sammlung Marli Hoppe-Ritter, Waldenbuch; Sammlung des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit, Berlin; Sammlung des Bundeslandes Hessen; Sammlung NordLB, Braunschweig; Sammlung Solomon Oppenheim Bank, Cologne; Kreissparkasse Weiblingen; Ernst & Jung, Stuttgart; Art Collection Rockefeller University, New York