Mona Lisa Travels. VI. Pilgrimage into the land of authenticity and back

EKATERINA DEGOT

PILGRIMAGE INTO THE LAND OF AUTHENTICITY AND BACK

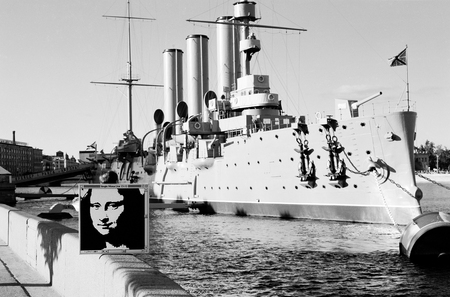

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: St. Petersburg. Two sailors, 2001.

L-Print, 120×150 cm

A central aspect of George Pusenkoff’s artistic work consists in thematizing the relationships between mass-production and the unique work.

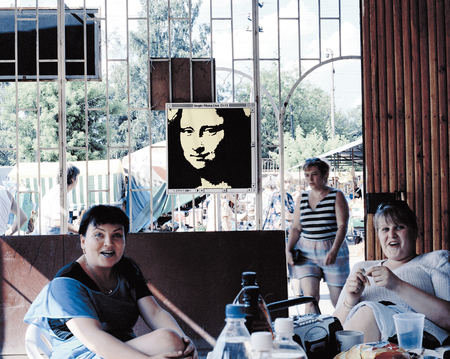

He first compiles quotations from art history on the computer in order to transfer them by hand onto canvas. Correspondingly, the distribution of such an art should also negate reproduction and medial communication and, in a manner just as old-fashioned, be made by hand. Therefore, with his project Mona Lisa Goes Russia, Pusenkoff has dispensed with the services of printing presses or Internet and in his own automobile driven one and the same picture — a paraphrase of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa — over the literally «bad streets» through cities and villages of Russia and installed it at the most various locations whose sole point in common consists in their not being institutionalized exhibition sites — at a bus stop, on the wall of a church, in the gambling casino, at a marketplace or in a museum depot which also serves not the presentation but the «private life» of pictures outside the public sphere.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia. Left: Red Square, 1998. L-Print, 40×50 cm. Right: St. Petersburg. Cruiser «Aurora», 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia. Left: The depot in the State Russian Museum. With paintings by Kazimir Malevich, 1998. Right: St. Petersburg. Nevsky Prospect, 1999. L-Print, 40×50 cm

The adequateness of Pusenkoff’s exhibition gesture consists, furthermore, in Russia’s understanding itself as being traditionally in opposition to the technoid and commercialized, as a space for human and spiritual authenticity, as a reserve for the genuine and the true: authentic, hand-painted shop signs; genuine feelings; a modest, not particularly decorative nature; or a dilapidated omnibus in which — in contrast to inhuman, technical perfection — the imperfection of the human is manifested.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia: Mona Lisa on September 11th 2001. L-print, 120×150 cm

Precisely this, however, permitted the «traveling exhibition» of Pusenkoff’s picture to come about every time without making a great stir and to blend into the easy-going, phlegmatic stream of life: The present-day inhabitants of the former Soviet Union are not so easily astonished and not at all surprised by the intrusion of a new visual image into their living space. The appearance of Mona Lisa within their field of vision is viewed benevolently but philosophically: Everything is transitory.

From the series Mona Lisa Goes Russia. Left: Kutusowsky Prospect, 1998.

L-Print, 40×50 cm. Right: Mona Lisa in Shadow, 1998. L-Print, 40×50 cm

In the course of his journey through Russia, the artist himself has become unavoidably submerged in that life through acquaintances, conversations and unique human contacts with passersby and residents: Authenticity obliges. All of this, however, in order to document this authenticity in photographs which show Mona Lisa’s stay in Moscow, in the environs of Moscow and in St. Petersburg. In the final analysis, these photos are also the goal of the project. And they are also what is exhibited in the realization of the project. Like Pusenkoff’s picture itself, the exhibition project is also characterized by a certain excess of self-sacrifice, by exertions that remain invisible.

Moscow. In front of Vera Muchina monument, 1998. L-Print, 120×150 cm

One might think that such photographs could also be easily created on the computer by simply mount- ing Mona Lisa into the respective landscape. In any case, Pusenkoff’s Mona Lisa might also have been a poster, which would at least have made the transport considerably easier. But no, it is a canvas on a stretcher, which not only complicates the transport but also the «glueing» when the action does not take place in an exhibition hall whose walls have special equipment for hanging pictures, or at least nails or hooks. As Pusenkoff demonstrates, the stretcher-frame can be carefully placed on the ground or fastened to the limb of a tree. One can stand it up on a row of bottles, fasten it with suction cups to the door of a limousine or give it to an elephant to hold. «Exhibiting» is variously transformed into «positioning», and it is always a question of an extremely fragile situation.

Left: St. Petersburg. State Russian Museum, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm.

Right: Moscow. Monument Park, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

As curious as it may sound, the attempt to exhibit a picture without hanging it on a nail even has a tradition in Russian art of the 20th century.

As an historical anecdote records, the great Kazimir Malevich encountered the no less ingenious Pavel Filonov in the 1920s as the latter with great effort pressed a freshly painted picture against the wall at the level of his head and declared to his baffled colleague that he strove to paint pictures which would hang from the wall all by themselves. To the question whether he had succeeded in this, he sorrowfully but honestly answered, «For the time being, they fall». Filonov’s utopia of the transtechnical exposition divulges the dream of pictures which have no substance and directly fuse with the wall without having to be specially held. They are pictures in the space of the cosmos but not in the space of a museum (not for nothing did Filonov always refuse to sell his works to museums or private persons). It is the squares and triangles of Malevich which hang in the white universe without a corresponding contrivance.

With their hooks, nails and even more refined hanging mechanisms, the walls of professional institutions for exhibitions lend art a virtually «divine» aid (so far as the mechanisms are carefully hidden from the eye) in permitting art to conquer gravity.

Left: Village of Kaftinsky Gorodok. The Lake, 1998. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Moscow. Golf Course, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: At the Gynecologist, 1998. L-Print, 120×50 cm. Right: City Hospital, 2000. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Filonov rejected such institutions, as he did every system of mediation. This dream (which, for example, Alexander Rodchenko also dwelled upon when he thought in terms of secret images projected directly onto the wall without brush and paints) would be partially realized in the practice of Soviet «public art» created between the 1930s and the 1980s and which until today — above all in the provinces — shapes the visual environment of Russia. In the Soviet Union, monumental art on the streets of the cities (frescos, posters, banners, i.e. pictures that more or less hang from the wall without effort) and freshly distributed mass art in the houses (newspaper photographs or book illustrations which are also easily held against the surface) was incredibly widely disseminated.

Ideally, this art which was so accessible to the viewer and which approached him so directly should provide a substitute for the distanced art in museums and, even more, in galleries.

On his journeys Pusenkoff encountered certain remains of this omnipresent art which existed outside the institutionalized sphere of art: the birch wood, for example, which was painted directly onto the wall of the staircase in a mass-produced house, as well as other examples of the naive designs of the 1960s and 1970s. To this series belongs as well the famous statue The Worker and the Kolkhoz Woman from the 1930s, which is not merely a sculpture but an intimidating sculpture awakened to life, which should also «hang in the air», as it were.

Left: Weekly Market, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Gorkovskaya Highway, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: St. Petersburg. State Russian Museum. Icon room, 1998. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Dresna. Lenin Monument, 1998. L-Print, 120×150 cm

In practice, this visual environment of an immediate intrusion of art into everyday life was either completely ignored or simply not noticed by the citizens of the Soviet Union — like bad weather that has lasted for a long while. Traditional museums could not only maintain their status but, quite the contrary, achieved a virtually fantastic and unbelievably high prestige, from the 1960s onward enjoying immense popularity among the Soviet people, who submitted themselves to standing in line for days in order to see the real Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. And a few lucky devils could even obtain the right to enter the closed depots in which the Russian avant-garde was kept — those who had dreamed of hanging in the air.

The present visual environment of Russian cities has caused this authority of the archive, of history, of the museum to waver or, more precisely phrased, to dissolve in the charm of the here and now. Like the realization of the dream of the Russian avant-garde, Russia is today full of «pictures that hang in the air».

Left: Moscow. Grizodubova Monument, 2001, L-Print. 120×150 cm.

Right: Moscow. Kremlin, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

The remains of the Soviet visual environment have literally been joined in the heavens by floating advertisements whose number burst all imaginable limits. In addition, countless mini-exhibitions of purchasable pictorial representations — from high-gloss magazines to pictorial hand-towels — are held at the most improbable locations.

In this manifold family, Pusenkoff’s Mona Lisa was like a nomad: in her case we would not even speak of the dissemination of an image, but of its journey.

In her smile lies the friendly openness of authenticity, but also the irony of distance. With such a smile, the tourist lets himself be photographed before the background of an unaffected exoticism, whose exoticism rests precisely in its immediacy.

Left: Orechovo-Zuevo. Bus Stop, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Moscow. Girl and Policeman, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: Kaliningrad, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: St. Petersburg. Limousines on Nevsky Prospect, 2000. L-Print, 120×150 cm

After her journey through the Russian reserve of unique and authentic experiences, Mona Lisa brings a whole stack of touristic snapshots with her and returns via the documentation of that which has been experienced — in the area of the technologized, the mass-produced, distanced and commercialized, because only there is contemporary art imaginable: for the experience of the here and now requires no representation.

Likino-Dulevo, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: Moscow. Monument Park, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm.

Right: Archangelskoje. Film Set of Pavel Lungin. September 11th 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: St. Petersburg. Casino «Premier», 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm.

Right: Dresna. Railway Platform, 2000. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Likino-Dulevo. Church, 2000. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: Village of Emilianovo, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Dresna. July 8, 2000. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Moscow. Conversation, 2001. L-print, 120×150 cm

Moscow. Yauzsky Boulevard, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: Moscow. On the roof, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm. Right: Moscow. Private Fitness Studio, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm

Left: St. Petersburg. Public Prosecutors, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm.

Right: St. Petersburg. Young Violinist, 2001. L-print, 120×150 cm

Moscow. In the Park, 2001. L-Print, 120×150 cm