(Dis)encapsulating Gulag

Setting the scene

There is a growing number of researchers interested in the reflection of Stalinist repression and the Gulag system in Russian museums. The recent issue of Problems of Post-Communism journal is particularly noteworthy here as it offers illuminating research informed by critical perspectives. For example, Sofia Gavrilova investigated how the local history museums of the cities where the camps were located directly deal with the representation of this horrifying period (Gavrilova 2021); Irina Flige researched conceptual approaches and exhibition designs used by Russian museums for exhibitions on the Soviet terror, revealing the typology of visualization models in more than a hundred museums of different subjects (Flige 2021); Andrei Zavadski and Vera Dubina focused on the main museum dedicated solely to the Gulag and convincingly showed that both repression and the Gulag are constructed as events related to the past (Zavadski and Dubina 2021).

The idea of this paper was inspired by a couple of arguments that seemed politically important, and from which I would like to build on in my own research. Firstly, it was argued that in the museums the Gulag is often presented as the past, encapsulated and reliably isolated from the present moment, something that completely belongs to the Soviet system and its history (Gavrilova 2021, Klimenko 2021, Zavadski and Dubina 2021). Secondly, the Gulag is often shown without references to the broader context, namely the Soviet economy where forced labor played a more than central role, and this basically decontextualizes repression (Klimenko 2021, Gavrilova 2021). I was interested in these two, let us say exhibition and conceptual techniques — isolation and decontextualization — because they make an unconditional contribution to the specific depoliticization of the Gulag, repression, and their raison d’etre.

In this paper, I would like to contribute to the existing literature and analyze how isolation and decontextualization of the Gulag function in relation to the 1990s, and present-day Russia. I intend to do this by looking at industrial enterprises built within the Soviet labor camp system and still functioning. Indeed, if we look closely, we will notice a number of industrial complexes that were built by the Gulag prisoners are still functioning, but with a key difference: in the Soviet times they used to be state-owned and placed within the framework planned economy with its imperatives to redistribute part of the income to maintain the public infrastructure of cities and regions where factories operated (Collier 2011: 79–83), now these enterprises are privatized, functioning within the framework of market economy, and it is the owner who receives the main rent from them, sharing it with the state within the framework of a public-private partnership (Matveev 2019).

Nornickel, formerly known as the Norilsk Industrial Complex, presents a particularly interesting example. The buildings and infrastructure of the industrial complex, and even more the entire city of Norilsk, were built by prisoners of Norillag, a camp specially organized by the NKVD Gulag. In the 1990s, this industrial complex was privatized by a financial and industrial group headed by oligarchs Mikhail Prokhorov and Vladimir Potanin. Now Nornickel is the world’s largest enterprise for the production of refined nickel and palladium (Nornickel About). Continuing the work of researchers I have mentioned above, I’m going to look at the Norilsk Museum, focusing on its permanent exhibition «Not Subject to Revision» dedicated to the Gulag and repressions. I would argue, looking simultaneously at the exhibitions and industrial history allows us to catch complex entanglement of state and culture. Thus, I’m planning to analyze the Norilsk Museum exhibition against the backdrop of the history of Norillag in a broader framework of the Gulag and Soviet «camp economy» (Ivanova 1997), as well as privatization of the Norilsk Industrial Complex in the 1990s.

Historical background: Mangazeya, Gulag, privatization

Norilsk presents a particularly paradigmatic example of a town whose history is inseparably connected to the functioning of the Gulag, and deeply touched by the privatization of city-forming enterprise in the 1990s. I would argue that the town’s history can tell a lot of exemplary stories of Soviet industrialization, as well as post-Soviet privatization, and basically illuminates the harsh entanglements of Soviet and early post-Soviet times and their meaning for present-day Russia. But before I touch on these periods, I want to make a few remarks on the prehistory of Norilsk that illuminates the extractive and colonial logic of the Russian and, later, Soviet state.

Norilsk is located in the Russian Arctic zone on the Taimyr Peninsula. Traditionally, these lands were and are still inhabited by the indigenous peoples of Siberia: Nenets, Selkups, Evenks, and Ket-people. At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, at the initiative of the tsarist administration, a permanent settlement of Mangazeya was founded here, which on the one hand, served as a colonial outpost for the advancement of the Russian voivodes deep into Siberia, and on the other hand it was an administrative center that collected tribute from the indigenous population (Kosintsev et al 2004). Mainly the Nenets and Selkups were obliged to pay furs imposed on them by the «sovereign yasak» to the treasury of the «Big White Tsar», who, in turn, undertook to protect local tribes and peoples from belligerent neighbors and resolve intra-tribal disputes and conflicts (Zhernosenko and Balakina 2011: 84). After the annexation of these lands to Russia, they continued to remain a resource base and a strategically important transport point. This story is indicative of the dynamics of Russian and Soviet colonialism towards indigenous lands which were driven by the logic of extraction.

The next stage of exploration of the region is connected to the Soviet times and begins with the expeditions of Nikolay Urvantsev in 1919–1926, which confirmed the presence of rich deposits of coal and polymetallic ores in the Putorana mountain range (Urvantsev 1981). Following this, in 1930, a large expedition of Glavtsvetmetzoloto went to these lands and came to the conclusion that a metallurgical plant should be built on the site of the deposits (Ertz 2003: 132). For the Soviet industry, the main interest here was the nickel contained in local ores, it is mainly used for smelting high-quality stainless steel, including armor, which was especially needed by the military industry. The stage connected to the plant construction was studied in detail by Simon Ertz, so in what follows I will rely on his research to tell about the functioning of the Gulag in Norilsk (2003).

In 1935, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR issued a decree «About Norilsk Nickel Industrial Complex Construction» (Ertz 2003: 129). It says that the NKVD Gulag is in charge of building the industrial complex, providing it with a 135 km long railway that would connect the various facilities of the plant, and, most importantly, creating a special camp for these purposes. Then, the head of the NKVD signed an order that outlined even more cumbersome goals: permanent exploitation of deposits, maintenance of the complex, and the development of an entire region (Ertz 2003, 133). According to Ertz, the whole project of Norilsk Nickel Industrial Complex construction corresponds to the established practice of assigning the Gulag, large-scale and long-term projects in remote, mainly northern and eastern, and underdeveloped areas of the USSR, which were of strategic importance for the country, for example, due to the presence of significant mineral reserves there (Ertz 2003, 133). Indeed, by 1935, the White Sea Canal (1933) had already been built by the Gulag prisoners and the construction of the Baikal-Amur Mainline had begun in 1932.

Thus, in 1935, the Norilsk Correctional Labor Camp, generally referred to as Norillag appeared and existed until 1956 (Ertz 2003: 128). At the cost of incredible efforts, by 1939 production was launched, and the industrial complex was overgrown with new facilities. In the same year, when the first hundreds of tons of rough nickel were smelted, Norilsk was awarded the status of a working settlement (Norilsk City About). During the Second World War, Norillag prisoners and civilian workers not only continued the active construction but also significantly intensified production volumes to produce enough nickel, which was used for tank armor (Galaov et al 2015: 9). In 1953 the Norilsk Complex produced 35% nickel, 12% copper, 30% cobalt, and 90% platinoids of the total production of these metals in the Soviet Union (Ibid). All this certainly points to the colossal role of the camp system for industrial modernization and the economy of the USSR. In her research dedicated to the role of the Gulag for the Soviet economy, Galina Ivanova points out that by 1940, the camp economy covered 20 branches of the national economy, among which non-ferrous metallurgy was one of the leading one.

The last thing I want to say in this section is about the privatization of the Norilsk Industrial Complex, as this indicates the very material basis of the emergence of oligarchs, new political and economic elite along with neopatrimonialism of contemporary Russia. In June 1993, by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation, the State Concern for the Production of Non-ferrous and Precious Metals Norilsk Nickel was transformed into the Joint Stock Company (JSC) Norilsk Nickel (Presidential Decree 1993). In accordance with the privatization plan, part of the shares of JSC was transferred to the labor collective of the plant, part of the shares was put up for sale at check auctions. More than 250 thousand people have become owners of shares of JSC Norilsk Nickel (Urozhaeva 2020: 198). The controlling stake in JSC, which is federally owned, was put up for collateral auction in 1995. According to its results, ONEXIM Bank, a financial and industrial group became the nominal holder of this controlling stake (Rozhkova 1997).

Later, in 1998, the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation published many facts testifying to the illegal privatization of state property (Urozhaeva 2020: 198). However, in June 2000, the Accounts Chamber submitted a new report, which was in fact aimed at some «rehabilitation» of the new owners of Norilsk Nickel, headed by Vladimir Potanin and Michail Prokhorov (Accounting Chamber 2000). Now according to the Forbes Rating of the richest people in Russia, Potanin ranks 2nd still owing Nornickel, and Prokhorov is 14th, having sold off all his assets in 2018 (Forbes 2021).

Museum narratives: Not subject to revision?

Being unable to fly to Norilsk, I asked A, a friend of mine who lived there to kindly make a video tour in the Norilsk Museum and take photos of objects and texts exhibited there. So A’s presence in the museum helped to bridge the distance and be my proxy body to which I’m deeply grateful. Another person I want to thank here is K, an ex-employee of the Norilsk Museum. Without her readiness to talk to me it would be impossible to get to know the number of details that helped to build my argument. Thus, my acquaintance with the museum was mediated by this generous participation.

In the museum there are two permanent exhibitions, one is dedicated to the prehistory of Norilsk and another to the Gulag, which simultaneously denotes the emergence of Norilsk as a settlement and city. I will briefly describe the first exhibition because it is important to understand the overall museum narrative and then I will focus on the Gulag exhibition more closely.

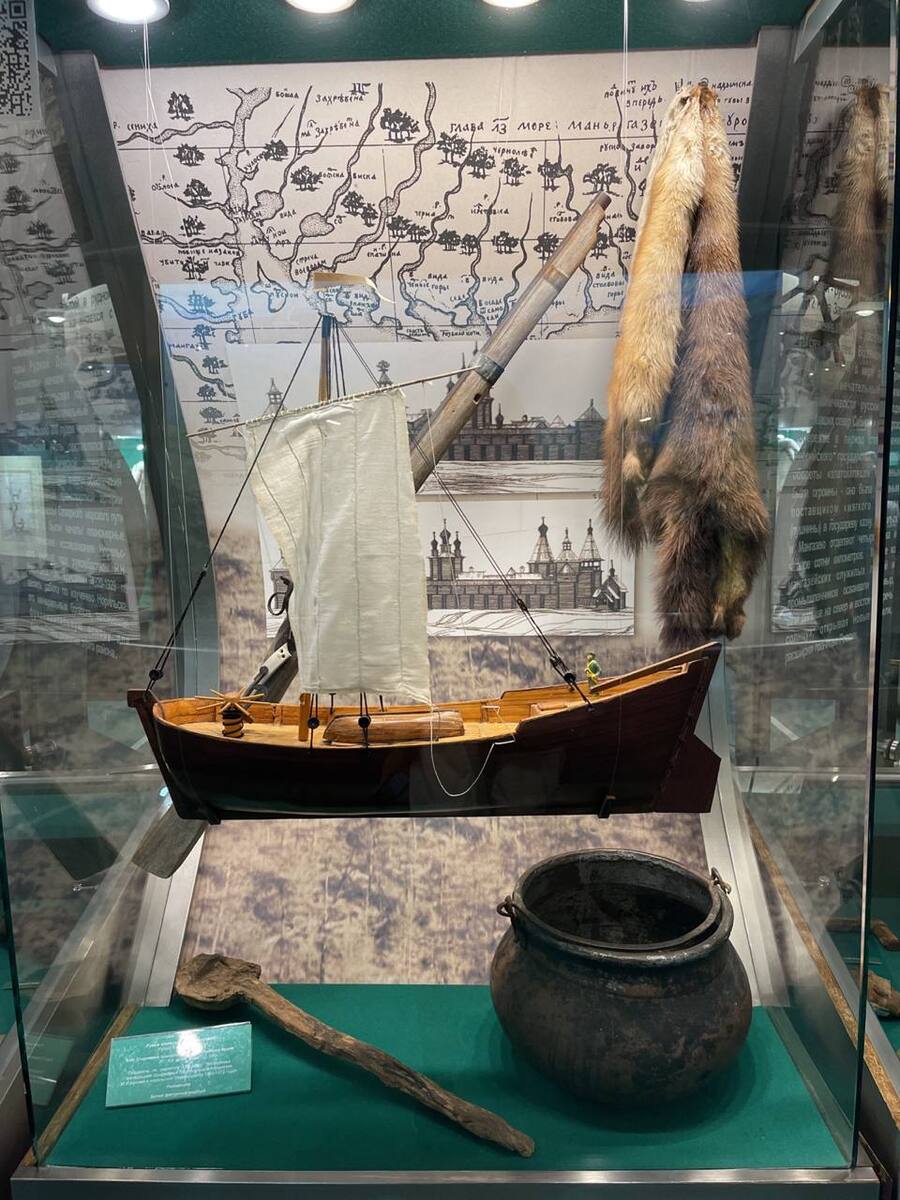

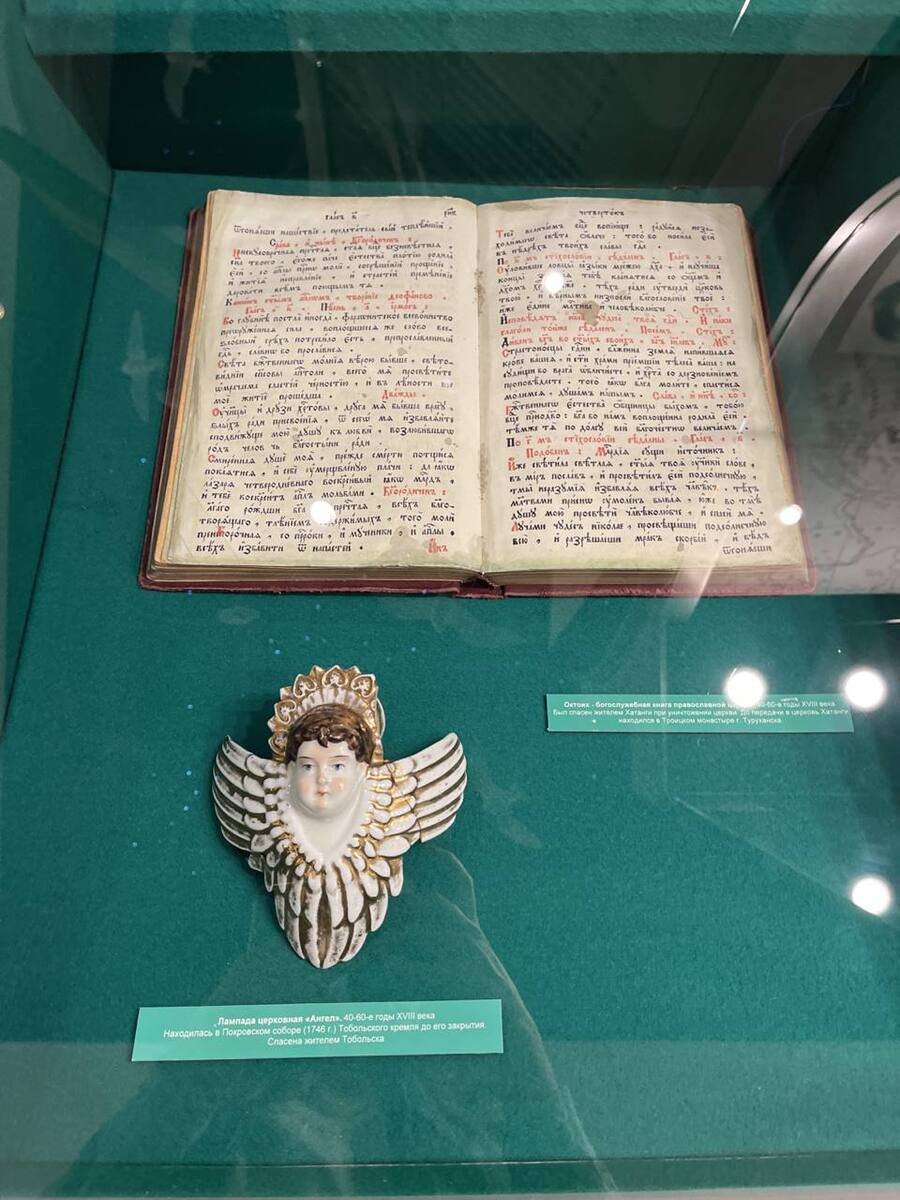

On the first floor, we can see an exhibition that consists of three thematically different but closely intertwined sections in the sense that they present a complex narrative about the prehistory of Norilsk, namely a period when this settlement has not yet existed. Along the perimeter of the floor, there are two sections about the nature of the Taimyr region, and about indigenous people. Here we can see photographs, stuffed animals, traditional dressings, yurts, tools, and household items. This exhibition surrounds the central showcase with historical milestones of the osvoenie of the region — the foundation of Mangazeya; various expeditions of the 16–19th century, presented as a heroic conquest of the north by Russians and the expansion of Russia; and finally, Soviet scientific expeditions. There we can see photos of people who participated in expeditions and exploration, measurement instruments, models of ships, compasses, letters, books, and maps.

It is remarkable that even the spatial organization of the overall exhibition transfers the implicit colonial message of epistemological hierarchy: passive nature along with indigenous people decoratively surround phallic and central showcase with «heroic Russian people» that brought with themselves progress and modernization to these wildlands. Thus, the whole narrative of Norilsk prehistory is structured around the tension between Russian conquerors and their constitutive others — Evenks, deer, yurts, polar bears.

On the second floor, which is divided into two levels, there are two exhibitions: one on the lower level is a temporary one dedicated to the functioning of the Norilsk Industrial Complex during WWII, and another, to the Gulag. Although the first exhibition is of direct relevance for my research I will skip it because it is a temporary one. The exhibition dedicated to the Gulag and repressions is titled «Not Subject to Revision» and was created in 2012. Since then, the exhibition has been repeatedly updated and supplemented.

The exhibition consists mainly of numerous documents, letters, photographs, testimonies of prisoners and their relatives. Along the two long sidewalls of the hall, there are about twenty identical black stands on which these documents are fixed. They merge into a single pattern and set the visual rhythm of the hall. Perhaps only a very meticulous and thorough viewer will be able to master the entire volume of the materials presented. Usually, people just walk along these walls, heading to the more diverse and attention-grabbing third wall along which three installations are built: the room of the camp’s political department, wooden stands with objects and documents belonging to prisoners, and a living room in which things made by prisoners are collected.

The room of the political department looks strict and gloomy, there is a table on which we can see a lamp, a telephone, and documents. The living room, in which there are objects manufactured by prisoners, refers to an ordinary Soviet apartment filled with unusual, and in a way uncanny objects. Unlike the political department, it looks cozy — there is a dining table covered with a tablecloth against the wall, embroidery with a beautiful landscape, and postcards hanging above the table. There is a bookcase behind the table. All these items were made by prisoners at different times. In addition, there are jewelry and dress in the room that belonged to the former prisoner, she wore them before being sentenced and sent to Norillag. In front of these installations, there is a construction wheelbarrow containing a prisoner’s jacket, shovels, a pickaxe, and other tools that were used in Norillag. This part of the exhibition, with installations and objects, certainly attracts greater attention of visitors than the stands with documents because it is far more spectacular and allows the emotional connection to the history of prisoners, their everyday life, and overall brutal condition.

However, before we move on, I will describe the contents of one of the stands so that it is clear how they are organized and what they tell the audience about. Documents and photos are fixed against a black background. One of the photos shows Stepan Novitsky-Mikhalev, an electrical engineer who served time in Norillag from 1938 to 1946. There is a certificate hanging next to it, which says that he submitted a number of rationalization decisions during the construction of the plant, 10 of which were implemented, for which he was officially thanked. Also on this stand, there are photos of other prisoners, certificates of their rehabilitation, letters, autobiography, and certificates issued by Norillag for hard work.

I was struck by the fact that this exhibition is not accompanied by a curatorial text that would give general information about the Gulag being a larger system within which Norillag existed, its structure, its role in the context of Soviet industry development, which would immerse the viewer in a broad political and economic context. In our interview, K, a former employee of the museum, confirmed that the curatorial text is missing and also noted that without a guide, the viewer can understand not that much in the museum’s expositions, because the objects in them are presented as references to the narrative that is usually told by a guide. Of course, if the viewer knows something herself, then she will be able to understand the exhibition and it will tell her a lot of interesting information, however, it might be difficult for an unprepared viewer to catch the history in its entirety. It is important to note here that such tightness is characteristic of local history museums, which are filled with objects, factual signatures to them, but the context for them is usually created only by the live speech of the guide and to hire a guide one needs to pay additional money.

I would argue, although the «Not Subject to Revision» exhibition carries out an important work of memory uncovering the archives, collecting new data about prisoners of Norillag, and integrating it into the exhibition narrative, as well as trying to connect the viewer emotionally to the history of Norillag, unfortunately, it misses a point of larger contextualizations of the Norillag within the Soviet economy and, in particular, Soviet project of industrialization. Without an explicit and easily accessible message, written in the form of curatorial text, for example, the viewer is unlikely to get an understanding of the Gulag was the result of not only the political atrocities of the Stalinist epoch that pushed people to the correctional camps but also the persistent economic needs of the state whose economy was largely reliant on forced labor.

However, what is the most intriguing of this exhibition as well as others dedicated to repressions and scattered across local history museums network (at least how we could make sense of them from the existing literature) is that they do not show the further fate of the objects built within the Gulag system focusing instead on the fate of people within the camps and afterward. I would argue that although the humanistic focus of such exhibitions is a remarkable achievement compared to the decades of the official silence, it is not enough to build the proper basement for the possible acknowledgment of the Soviet labor camp economy and its social, political, and economic consequences. I would insist that solely humanistic focus can be or already is easily co-opted by the current political regime for the purpose of isolating a nationwide tragedy and leaving it to the past, which is in fact far away from being hermetically isolated from the current regime. In the concluding part, I will try to explicitly demonstrate the link of Soviet industrial development to the emergence of neopatrimonial post-Soviet state exactly through the material assets left as heritage.

Questioning why the liberal reforms of the 1990s in Russia led to «the hell of patrimonial ‘crony capitalism’», Vladimir Gel’man insists that «after the collapse of the USSR, the domination of neo-patrimonial political institutions was established in Russia and a number of other countries» which were largely purposely and deliberately created in the interests of the ruling groups and designed to consolidate their political and economic dominance (Gel’man 2015: 36). Indeed, as Ilya Matveev argues, «The contradictions of the planned economy, as well as ideological erosion, the loss of the party’s ‘combat mission’ led to the growth of informal relations of the patrimonial type within the Soviet economic system and the parallel growth of the shadow economy in the late USSR. Gorbachev’s reforms launched the dominant project of the post-Soviet elites — the project of extraction of state resources» (Matveev 2015: 27). As a result, those who established control over the resources of the state turned out to be the new post-Soviet elite, the oligarchs, who still own the largest assets that were privatized during the transition from a planned to a market economy.

It is not difficult to assume that the largest tangible assets that were owned by the Soviet state were industrial facilities and the infrastructure adjacent to them, a huge proportion of which was built in the Gulag system. Thus, I would argue the Soviet prison-industrial complex, which operated in the context of a planned economy and set the dynamics and pragmatics of massive repressions, has a deferred effect extending to the post-Soviet period — namely, the emergence of a new economic and political elite. It is for this reason that I insist that a humanistic focus in the representation of repressions is not enough, it is necessary to pay more attention to facilities and material infrastructure that do not allow us to isolate so easily the Gulag from the present moment, presenting it in a time capsule limited to the dates of Stalin’s reign.

Nevertheless, we cannot turn a blind eye to the risks and difficulties associated with the public display of the stories that haunt the troubled period of the 1990s. Indeed, when I asked K if Norilsk Museum had ever done the exhibitions dedicated to the 1990s or talked anything about Nornickel in respect to this time frame, the answer was negative. She explained that telling the story of Nornickel is like telling the story of those who cannot be named. «You can’t talk about them out loud.» This is something that everyone knows, but something that cannot be displayed within a public space, a museum.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, I would like to note that a critical study of the representation of the Gulag in Russian museums is a step towards asking more often, what are we allowed to know about the history of industry and modernization in Russia, and why are we allowed to know this and not something else. In fact, large-scale repressions carried out largely for economic purposes are not the only dirty secret in the history of the industrial successes of the USSR, and then Russia. As it might be clear from the history of the appearance of Norilsk and from my brief retelling of the ethnographic exhibition at the museum, economic and industrial breakthroughs are inextricably linked with colonial violence, the seizure of territories, and the extraction of resources. And unfortunately, this is not a thing of the past. That is why in order to deal with ongoing violence, it is crucial to acknowledge the past which is not a bygone.

References

Accounting Chamber (2000). Proverka privatizatsii federal’nogo paketa aktsii RAO Norilskii Nickel [Verification of the Privatization of the Federal Stake in JSC Norilsk Nickel]. Retrieved from https://ach.gov.ru/checks/proverka-privatizatsii-federalnogo-paketa-aktsiy-rao-norilskiy-nikel-i-vklada-rao-norilskiy-nikel-v-

Association of Memory Museums. Muzei istorii osvoenia i razvitia noril’skogo promishlennogo rajona [Museum of the History of Exploration and Development of Norilsk Industrial Region]. Retrieved from http://memorymuseums.ru/museum/muzej-istorii-osvoeniya-i-razvitiya-norilskogo-promyshlennogo-rajona

Collier, S.J. (2011). Post-Soviet Social: Neoliberalism, Social Modernity, Biopolitics. Princeton: Oxford.

Ertz, S. (2003). Building Norilsk. In Paul R. Gregory and V. V. Lazarev (Eds.), The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

Flige, I. (2021). Visualizations of Soviet Repression and the Gulag in Russian Museums: Common Exhibition Models. Problems of Post-Communism, DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2021.1987268

Forbes (2021). 200 bogateischikh biznesmenov Rossii — 2021 [200 Richest Businessmen of Russia — 2021]. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.ru/rating/426935-200-bogateyshih-biznesmenov-rossii-2021-reyting-forbes

Galaov, R. B., Pelipenko, E. V., Koletchko, S.S. (2015). Istoria osvoenia i perspectivi razvitia mineral’no-sir’evoi basi GMK Nornickel [History of exploration and prospects of development of the mineral resource base of MMC Nornickel]. Gornii Journal [Mountain Journal], 6, 7–11. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17580/gzh.2015.06.01

Gavrilova, S. (2021). Regional Memories of the Great Terror: Representation of the Gulag in Russian Kraevedcheskii Museums. Problems of Post-Communism, DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2021.1885981

Gel’man, V. (2015). «Porotchnii krug» postsovetskogo neopatrimonialisma [«The Vicious Circle» of Post-Soviet Neopatrimonialism]. Obschestvennie nauki i sovremennost’ [Social Sciences and Modernity], 6, 34–44.

Ivanova, G. (1997). GULAG v sisteme totalitarnogo gosudarstva [GULAG in the System of the Totalitarian State]. In A.N. Sakharov (Ed.), Dokladi Instituta Rossiiskoi Istorii RAN 1995–1996 [Reports of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 1995-1996]. Moscow: IRI RAS.

Klimenko, E. (2021). Politically Useful Tragedies: The Soviet Atrocities in the Historical Park (s) «Russia — My History». Problems of Post-Communism, DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2021.1974884

Kosintsev, P. A., Lobanova, T. V., Vizgalov, G. P. (2004). Istoriko-ekologitcheskie issledovaniya v Mangazee [Historical and ecological research in Mangazeya]. Materiali VII Sibirskogo simposiuma [Materials of the VII Siberian Symposium], 36–39.

Matveev, I. (2019). Krupnii bisnes v putinskoi Rossii: starie i novie istochniki vliyaniya na vlast’ [Big Business in Putin’s Russia: Old and New Sources of Influence on the Government]. Mir Rossii [World of Russia], 28 (1), 54–74. DOI: 10.17323/1811-038X-2019-28-1-54-74

Matveev, I. (2015). Gibridnaya neoliberalizatsia: gosudarstvo, legitimnost’ i neoliberalism v putinskoi Rossii [Hybrid Neoliberalization: The State, Legitimacy and Neoliberalism in Putin’s Russia]. Politia [Politia], 4 (79), 25–47. Nornickel. About Company. Retrieved from https://www.nornickel.ru/company/about/

Norilsk City. About. Retrieved from https://www.norilsk-city.ru/about/1242/index.shtml

Norilsk Museum. History of the Museum. Retrieved from https://norilskmuseum.ru/istoria-musea

Presidential Decree. (1993). Ob osobennostyakh aktsionirovaniya i privatizatsii Rossiiskogo gosudarstvennogo kontserna «Noril’ski Nickel» [About the peculiarities of the corporatization and privatization of the Russian State Concern «Norilsk Nickel»]. Retrieved from https://docs.cntd.ru/document/9004466/titles/9P2V2D

Rozhkova, M. (1997). ONEXIM prihodit kak khozyain. [ONEXIM Comes as the Host]. Retrieved from https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/182127

Urozhaeva, T. (2020). Privatizatsia gradoobrazuyuschikh predpriyatii Krasnoyarskogo kraya v 1990 — natchale 2000 [Privatization of the Citi-forming Enterprises in Krasnoyarsk Region in 1990-2000]. Materiali Vserossiiskioi nauchno-teoreticheskoi konferentsii [Materials of the All-Russian Scientific and Theoretical Conference], 198–204. Irkutsk: Ottisk Publishing House.

Urvantsev, N. (1981). Otkrytie Norilska [Discovery of Norilsk]. Moscow: Nauka.

Zavadski, A. and Dubina, V. (2021). Eclipsing Stalin: The GULAG History Museum in Moscow as a Manifestation of Russia’s Official Memory of Soviet Repression. Problems of Post-Communism, DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2021.1983444

Zhernosenko, I.A. and Balakina, E.I. (2011). Kultura Sibiri i Altaya [Culture of Siberia and Altai]. Banaul: Publisher Zhernosenko S.S.