Phantom Bodies and Simulated Tactility

In the previous chapters, the body appeared primarily as an active participant in interaction—touching, moving, responding—whereas here it becomes both image and material. In the selected works, artists recreate bodies anew: reconstructed, artificial, assembled from silicone, wax, fabric, metal. They appear alive, though no life is present within them. It is in this paradox—presence without the one who is present—that phantom tactility emerges.

The viewer responds to the artificial as if it were alive, sensing the familiar qualities of skin, its fragments, softness, warmth, or vulnerability, even when the material itself is inert. These works engage the memory of the body: bodily sensitivity continues to exist without physical contact. Tactility shifts into the imagined, turning into a field of sensory illusions and empathic projections.

Contemporary artists do not imitate the body literally—they explore its capacity to become metaphor, vessel, and a form of experience. Their work shows how the body continues to live within material: compressing, decaying, flowing. In this, a new corporeality takes shape—hybrid, artificial, yet emotionally truthful. This body does not require touch, because it becomes touch itself—an image that evokes a response.

The Body in Transformation

In contemporary art, the body often appears at the moment of deformation, disintegration, or change. Artists abandon the fixed image of the human, approaching corporeality as a state. Here, transformation is understood not as a metamorphosis of form but as an experience: the body is felt as a fluid material capable of changing while still retaining its sensorial nature.

From the soft organic forms of Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois to the bodily shells of Francesco Albano and Berlinde De Bruyckere, these works explore how the body can be fragile, vulnerable, and still deeply resonant. They capture the moment of becoming, when the material turns emotional, and the skin becomes the boundary between the inner and the outer.

Nue couchée, 1969–1970 — Dorothea Tanning

Tanning’s soft sculpture balances between body and object, between movement and stillness. The smooth, sewn fabric form, stuffed with wool, resembles a creature or a tree trunk with severed branches.

Tanning moves away from literal representation and creates an organic shell in which the living is sensed through details and contours. There is sensuality without eroticism; presence without a concrete human figure. Tanning shows how form can be bodily without depicting the body directly — how matter itself begins to feel alive.

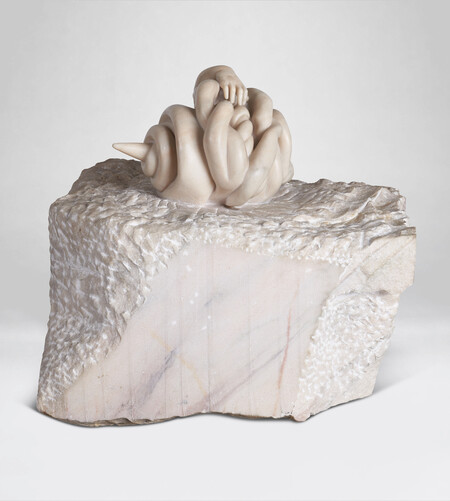

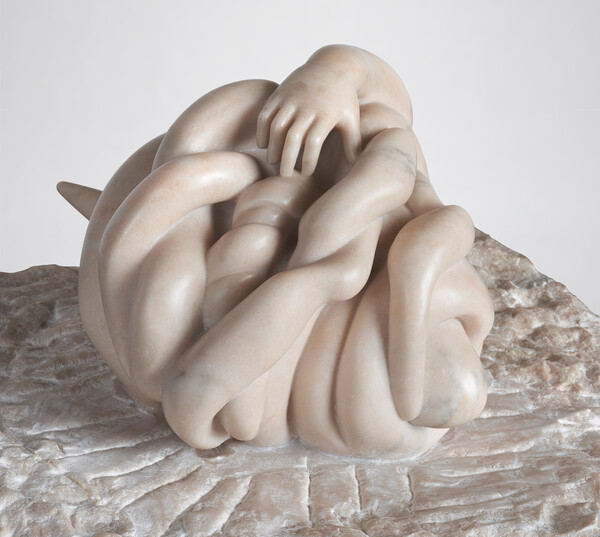

Nature Study, 1986 — Louise Bourgeois

In Nature Study, cold pink marble turns into flesh. Bourgeois makes the stone appear soft and tender by placing a twisted mass atop a rougher surface. The sculpture resembles a snail shaped from a hand twisting onto itself.

The work holds a tension between the inner and the outer: the natural structure of the marble remains visible, yet it is shaped by the artist into something with human traits. This creates the impression of a living being without a clearly defined body; a single hand and its spiraling movement are enough for the viewer to perceive it as corporeal and to understand the sensation of being curled in on oneself.

Couple, 2002 // The Couple 2007-2009 — Louise Bourgeois

In the two works titled Couple, the body is depicted differently but becomes an image of dependency and attachment. Two bodies, locked in endless embrace, hang suspended in the air, balancing between heaviness and lightness, merging and simply coexisting. In the soft pink fabric version, the warmth of textile evokes the familiarity of skin.

In the aluminum Couple, the body loses its softness and becomes a polished cast cocoon. The material is cold, yet the form preserves the same tension — the intertwining, the impossibility of separation. Bourgeois translates emotional states into physical form: closeness becomes structure, dependency becomes shape. The body loses individuality but gains a new unity, becoming a symbol of an inseparable human experience.

«Lange eenzame man», 2010 // «Arcangelo glassdome III», 2023 — Berlinde De Bruyckere

De Bruyckere creates bodies that appear almost too alive to be wax sculptures. Her works sit on the boundary between the sacred and the corporeal, as though religious iconography merged with an anatomical study. High Lonely Man — an elongated figure — seems at once sleeping, dying, decomposing, and frozen in a moment of bodily transformation.

The artist deliberately conceals faces, replacing individuality with universality, allowing the body to speak for itself. Blankets, coverings, and skin become thresholds between interiority and exposure, between vulnerability and comfort. In Archangel in a Glass Dome III, this effect intensifies: the legs sealed under glass are perceived as a relic. Berlinde De Bruyckere’s sculptures remind us that fragility can be monumental.

On the Eve, 2013 // When Everyday Was Thursday, 2010 — Francesco Albano

In Albano’s sculptures, the body seems to dissolve into its own shell. Forms sag, stretch, and flatten, as if the skin has separated from what once filled it. These images suggest bodies without support, without a center, existing in a state of collapse.

Albano does not depict suffering but a physical manifestation of inner fracture. His figures lack faces, gender, or age, yet their folds and drooping contours express human vulnerability. Here, skin becomes a material of memory — it holds imprints and traces of life, though life itself has left. The sculptures resemble skins shed from the body, or shells that contain only the echo of presence.

In his work, the body stops being an image of a person and becomes the matter of experience — compressed, thinned, yet still responsive.

Across all these works, the body ceases to be a stable form and becomes a process of change. It is fluid, soft, compressible, decaying, yet still sensorial. The artists show the body not as a representation of a human but as the material of experience — a substance capable of storing memory of life and of touch, which explains its facelessness. Here, the living and the non-living merge: fabric and marble, wax and aluminum, skin and air become equal mediums of corporeality. The body exists not as an object but as a state — mutable.

The Body as Object

Another mode of the body’s presence is its consideration as a thing, an object, a material, a surface. Artists work with imitations of skin, organs, and traces of life, turning the corporeal into an object of observation and reflection.

From Alina Szapocznikow’s lamps to the silicone works of Maayan Sophia Weinstub and the sculptures of Holly Hendry, the body becomes an artifact that preserves the memory of the living. In these works, the viewer encounters a paradox: the non-living evokes a sense of closeness, and the artificial conveys vulnerability. This is where the effect of phantom corporeality arises—contact that happens not through skin, but through visual and emotional sensation.

Lamp, 1967 // Lamp, 1970 — Alina Szapocznikow

In her lamps, Szapocznikow fuses the body with the mechanics of an object. Cast body parts initially resemble abstract color patches or plant-like forms transformed into sources of light. She literally turns the body into a functional object, yet this gesture does not dehumanize; instead, it reveals the body as part of the environment, part of nature.

Dessert III, 1971 // Petite Dessert I, 1970–1971 — Alina Szapocznikow

In the Desserts series, the body becomes an edible image—a metaphor of desire and consumption. Body fragments, reminiscent of marshmallow or meringue, appear appetizing at first, and then, once recognized as human parts served on plates, evoke unease. These «treats» provoke an almost physical reaction through their vivid realism. Szapocznikow exposes the duality of our relationship to the body—between pleasure and fragmentation. Having experienced illness and the awareness of her own mortality, she materializes the anxiety of corporeal existence, preserving it in the form of seduction and irony.

Objects, 2021 — Manuela Benaim

Benaim created a mirror whose surface is cast from an armpit—a part of the body usually concealed. The embedded hair and texture of skin transform the mirror into a living surface in which the reflection is not an idealized image, but the reality of the body itself.

She shows how an item meant as a tool of self-perception becomes a boundary between the real and the imagined body. The mirror does not reflect beauty—it reflects doubt, vulnerability, and imposed norms. Through merging the intimate with the utilitarian, Benaim collapses the distance between body and object, turning the body into a material that looks back.

Bed, 2022 — Maayan Sophia Weinstub

Weinstub’s work is a bed whose sheets are replaced with skin. The surface appears alive yet is marked by bruises and traces of pain. The artist transforms a familiar symbol of rest and comfort into a site of vulnerability and suffering.

The work speaks of trauma hidden within the everyday—of how violence can occur precisely where safety is expected. The body is absent, but its imprint is palpable in the material, in the marks, in the damage. This skin-bed becomes an image of the body’s memory, which retains pain longer than the mind.

The piece resists neutral contemplation: the viewer feels as if intruding into someone else’s intimate space, becoming a witness to what has been endured.

Let There Be Light — Breathing Bulbs Installation, 2024 — Maayan Sophia Weinstub

In this installation, Weinstub brings together light and breath—two symbols of life. Elastic bulbs inflate and deflate, mimicking human breathing.

She merges technique with the organic, drawing a parallel between the human body and a mechanism. The bulbs breathe, but artificially; they live, yet without a body. This synthetic rhythm is both soothing and unsettling, as we recognize our own fragility within it.

Weinstub creates a poetic image of artificial life. Watching the movement of light elicits a physiological response, as if the viewer begins to breathe in sync.

Gum Souls, 2018 — Holly Hendry

Gum Souls, 2018 — Holly Hendry

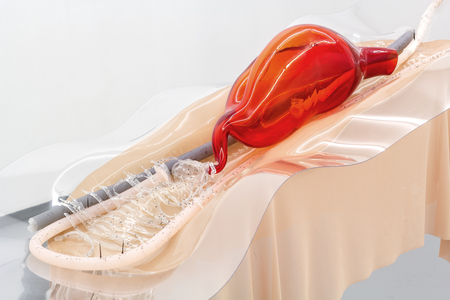

In Gum Souls, bodies appear as slices, diagrams, and fragments of anatomy merged with mechanical elements. Flat reliefs made of pigmented plaster and cement recall medical illustrations and the insides of toys.

Hendry presents another type of corporeality—mechanized yet not lifeless. Her Gum Souls are hybrids of human and machine, both ironic and unsettling. Plaster, metal, and plastic emphasize the synthetic nature of the contemporary body, dependent on technology and infrastructure.

She literally opens up the architecture of the body, revealing that beneath the skin lie no longer muscles but wires, pipes, seams. This is the body of the 21st century—integrated into systems yet still capable of feeling.

Notes to Self, 2024 — Holly Hendry

In Notes to Self, Hendry connects the mundane space of the office with the inner world of the body. Sheets of paper pinned to the wall morph into biological forms fused with bodily materials. This metaphor of to-do lists and reminders becomes an image of mental and physical exhaustion, where the body dissolves into informational noise.

Using glass, metal, ceramics, bronze, and paper, Hendry shows how internal processes—breathing, blushing, digestion—project themselves outward. The body becomes dispersed in space, and its presence phantom-like: we see not a person but the traces of a life, a system of signals and reactions. This merging of mental and physical, living and material, creates the sense that the body «speaks» through things.

The Exhaust’d, 2023 // Watermarks, 2024 — Holly Hendry

In The Exhaust’d, the body and machine merge into a single respiratory system. Metal pipes, glass forms, and a cast-metal ear create a complex structure in which air, sound, and energy circulate. Hendry equates car exhaust, breathing, and hearing—different forms of exchange between inside and outside.

Material becomes a medium of sensation. The work is constructed like an anatomical maze where the mechanical and organic fuse. It is a phantom reconstruction of processes. The body exists as function, movement, circulation—no longer anatomical but conceptual.

In Watermarks, Hendry continues this idea. She turns the façade of a museum into a body with internal circulation—a network of channels, pipes, and systems reminiscent of human anatomy. In its transparent vitrines, the architecture seems to pulse, as if revealing its inner organs. Hendry merges the architectural, the natural, and the anatomical, creating the feeling that even a building breathes, flows, and senses.

The motif of water strengthens the association with liquid as the basis of life: currents, tears, blood, ocean waves. Water becomes a metaphor for corporeality, dissolving the boundaries between the living and the non-living, the human and the infrastructural. This work embodies the idea of the phantom body—a body that does not exist literally yet is felt through space, material, and metaphor. The sculptures, resembling pipes and organs, do not imitate a person but evoke a physical response, as though we are glimpsing a cross-section of our own body. Hendry turns the artificial into the living, architecture into an organism, and observation into sensory participation.

In works where the body is presented as an object, it becomes a material carrier of memory, emotion, and experience. The body turns into a thing yet does not lose its human essence—on the contrary, it becomes even more present through the object.

From Szapocznikow’s lamps to Hendry’s mechanical systems, the body becomes architecture, instrument, and surface through which the act of existence becomes visible. The object becomes an extension of the living.

Amorphous Body

Here, the body loses its contours, becoming a substance without shape, gender, or boundaries. It stretches, dissolves, and merges the organic with the technological. These are bodies of the future: hybrid, synthetic, sensorial.

Hannah Levy and the duo Pakui Hardware explore how artificial materials can reproduce the sensations of the living. Their sculptures appear wet, soft, breathing—though they are made of silicone, metal, and plastic.

The amorphous body is a metaphor for phantom tactility: it does not require touch, because it evokes the sensation of touch on its own.

Untitled, 2024 // Untitled, 2020 — Hannah Levy

In her untitled works, Levy creates hybrids of the bodily and the utilitarian. Cold metal structures resemble handrails, prosthetics, pieces of furniture—objects designed to support the body when it weakens. Yet in her interpretation, they enter into dialogue with silicone «skin, ” translucent, moist, seemingly alive.

These forms appear functional but prove useless: they do not assist but confuse, they do not support but undermine the very idea of support. Levy seems to suggest that any body is temporary, and that any mechanism built to protect it will, eventually, lose its meaning.

In this encounter between the artificial and the living, a new sense of corporeality emerges—when touch is possible but not desired, when skin becomes a surface of experience.

Untitled, 2023 // Untitled, exhibition view Pendulous Picnic, 2020 — Hannah Levy

In the works presented in Pendulous Picnic, Hannah Levy transforms design objects—chandeliers, loungers, brackets—into strange, flexible bodies. Metal bends like muscle, and silicone elements resemble skin: stretched, translucent, porous, wrinkled.

This series can be read as an almost grotesque parody of decorativeness: the forms appear functional, yet each is too sensuous to be simply an object.

Levy speaks of the contemporary body as a designed object—shaped by cultures of care, fitness, aesthetics, and control. Her materials, steel and silicone, combine coldness with delicacy, turning the artificial into flesh.

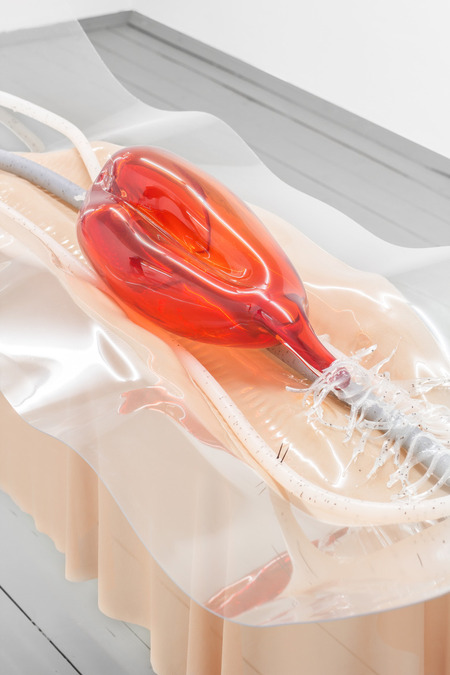

The Return of Sweetness, 2018 — Pakui Hardware

The duo Pakui Hardware investigates the boundaries between organism and machine. Their sculptures evoke internal organs, plants, laboratory vessels—hybrid forms in which life and technology intertwine into a single organism.

The Returning of Sweetness turns to the theme of metabolism—both a biological and an economic process. The sculptures appear as if seen from inside the body: transparent, fluid, filled with imagined liquid. But this is not real biology; it is its synthetic counterpart, engineered from technological materials.

In this amorphous substance, the familiar boundary between living and non-living dissolves. The artists show how the contemporary human increasingly becomes a system—regulated, recalibrated—where even the sense of one’s body becomes a product of engineering.

The Return of Sweetness, 2018 — Pakui Hardware

In these works, where the body appears amorphous, the artists explore how contemporary materials imitate the living — creating illusions, offering form without form. There is no longer a clear distinction between human and device, nature and technology — only a unified corporeal environment existing at the level of sensation.

Fragments and Traces of the Living

Here, the body is no longer a whole image — it breaks apart into fragments, into isolated gestures, textures, and materials that retain its phantom presence. Artists turn not to the body as a figure but to its remnants: hair, skin, fur, even bone. These elements no longer depict the human form directly, yet they continue to provoke bodily responses.

In such works, the viewer perceives the body through the recognition of a detail, through the feeling that this texture — or even this kind of movement — once belonged to something alive.

L’emur, 2020 // Caress, 2018 — Pfeifer & Kreutzer

In the duo Pfeifer & Kreutzer, mechanical car wipers move slowly across furry, woolen surfaces, as if stroking a living pelt. The repeated motion is at once gentle and unsettling: it imitates care, a caress, yet in mechanical execution it becomes emotionless. In their works, the phantom of the body emerges not through depiction but through the gesture of touch performed without a human subject. There is a cold irony in this: tenderness is mechanized, tactility replaced by the movement of a device.

Here, the viewer feels corporeality not through vision but through the body’s own recognition of the gesture — as if sensing a touch. It is an experience of simulated contact: sensation without a body, a gesture without agency.

Hair House, 2013 — Jim Shaw

In Hair House, Shaw returns to the tale of Rapunzel, where hair symbolizes dependence, vulnerability, and power. By translating this image into a material object, the artist turns hair into architecture. A material usually linked to the body becomes a structural element from which shelter is built.

Hair here is no longer a metaphor of beauty but a carrier of memory—a residue in which the shadow of presence remains. It is the body reduced to matter, to trace, to a substance that becomes form.

Naiad Fountain, 2021 — Julia Belova

In her work, Julia Belova engages with themes of corporeality, sanctity, and death, creating porous, densely textured structures in which recognizable parts of the body—ribs, hair, tendrils—are woven into a mass. In Naiad Fountain, synthetic hair imitates flowing water, producing a sense of movement frozen in time. In another work, Blue Grave, ceramic skulls and porcelain body fragments merge with soft materials, forming a fusion of the living and the dead, the organic and the artificial.

Belova creates hybrid bodies where sensuality and decay, empathy and the coldness of material coexist. The body is already dissolved into matter, but remains as a ghost of form, a phantom.

Blue Grave, 2022 — Julia Belova

These works share an urge to restore corporeality through trace. If in earlier examples the body acted — touching, breathing, interacting with the viewer — here it is replaced by matter that preserves its rhythms. These are bodies without anatomy, where gesture, texture, and mechanical motion become forms of phantom touch.

If one compares these works with performative approaches, in performance the living body once triggered emotional response and served as the medium of experience. In today’s practices, this response is often transferred onto the artificial. Artists create bodies that do not live, yet are perceived as living.

These bodies exist at the threshold of recognition: they may be soft, fragile, translucent, but they always provoke a physical reaction — an urge to touch, or to recoil. This is a new form of corporeality based not on actual contact but on the sensation of possible touch, on the memory of a body that is no longer there.

In this phantom presence, corporeality becomes a universal artistic language. It speaks of fragility, vulnerability, and the desire to feel. Contemporary artists — from Louise Bourgeois and Alina Szapocznikow to Hannah Levy and Pakui Hardware — do not depict the body; they recreate the sensation of its closeness, showing how the artificial can evoke the living.

Here, the body dissolves into material, into silicone, into mechanism, into the light of a lamp, or appears only in fragments. A new space of tactile perception emerges — phantom, yet real in its emotional resonance. It is precisely in this interval between body and image, between the living and the non-living, that contemporary art restores the capacity to feel — not through touch, but through recognition.