THE EVALUATION OF COLLECTIONS BY AFRICAN MUSEUMS

Content:

Section 1…. Concept Section 2…. A brief background about looting of African artifacts during the period of European colonialism. Section 3…. Collection assessment: A case study of Uganda Museum, Buganda Museum, Igongo Museum, Great Lakes Museum, Nairobi National Museum and Rwanda Museum. Section 4…. Some of the internationally recognized traditional and contemporary African artists who engage with themes of heritage and restitution. Section 5…. Technological applications in African museum settings Section 6…. Conclusion Section 7…. List of image sources & Bibliography

Section 1:

CONCEPT

The evaluation of collections by African museums represents a crucial movement in the global cultural landscape, catalyzed by the need to decolonize knowledge, restitute looted heritage, and redefine the purpose of museums in contemporary African societies. Museums worldwide are undergoing a profound transformation; this involves re-examining their responsibilities towards the collections. This process is particularly critical for the African museums, as many institutions hold collections with complex histories shaped by colonial legacies and historical power imbalances. There is a growing recognition of the need for museum practices that not only preserve collections but also address historical gaps, contextualize acquisition histories, and foster more equitable relationships with source communities.

This visual research proposes a comprehensive evaluation framework designed to meet the specific needs and contexts of African museums, aiming to empower them in their roles as dynamic centers of public engagement and cultural heritage. The visual study positions this evaluation not as a mere administrative process, but as a practice that is reshaping cultural identity, historical understanding, and international relations. «These works form an integral part of defining our identity and personality as family, as African family. We talk to them. They talk to us. We touch them at certain moments of our lives, from birth through life to death. It is through them that the living spirits of our people, of our history, of our culture interact and interface with us. They are not there, hence the void in our minds and in our hearts. We continue to cry for them to come back home, to complete that cultural, spiritual space» (Theo-Ben Gurirab)

The visual research investigates how African museums are moving from being passive storages of colonial collections to becoming active agents in reinterpreting and reclaiming their cultural narratives. The focus was put on: Looting of African artifacts and rethinking the power dynamics of their acquisition, assessment of museum collections, the African artists who engage with themes of heritage and restitution, as well as the technological applications in African museum settings.

There are numerous triggers for the topic selection and among them included the need for African-centered approaches to collection management. In order to simplify the research process, the following research question was formulated: How African museums implementing collection evaluation frameworks that address both international standards and local cultural contexts? For the smooth flow of research, the Hypothesis was also clearly stated: African museums are creating enormous evaluation models that integrate international museum standards with indigenous knowledge systems and address colonial legacies. The material selection of the visual research was based on the institutional reports, regional case studies, as well as publications from the past decade featuring the history of African museums.

Section 2:

A brief background about looting of African artifacts during the period of European colonialism

According to Sarah V. B. (2022). Collectors’ motivations were diverse: sometimes removing objects was motivated by a show of power, curiosity, religious purposes, and so forth. Often collected objects played important roles in the promotion of empire, illustrating the so-called primitiveness of African peoples, thus justifying the need for a colonial «civilizing mission.» Some of the objects were violently plundered during the conquest and «pacification» of colonies by European military forces. The best-known example is the plunder of the capital of the kingdom of Benin in 1897 by a British «punitive» expedition, during which the now famous Benin bronzes were removed from the royal court. The bronzes were military trophies and eventually became prestigious museum objects.

«The interior of Oba’s palace during the punitive expedition, with the looted Benin Bronzes in the foreground 1897», Paul Hudson, 2022.

It should be noted that in 1897, there was several attempts made by British expedition force to penetrate the Benin city during the traditional festival. They invaded, destroyed the property, and looted the loyal palace. A round 10,000 artifacts such as wood items, ivory, coral to mention but a few were stolen. These stolen items were later auctioned off to fund the military operations as well as stocking the Western museums and collections.

«Members of the punitive expedition in Benin surrounded by objects looted from the royal palace 1897» Paul Hudson, 2022.

It was clearly noted that after the killing of a smaller expedition of British officials and African carriers led by James Phillips, the Punitive Expedition to Benin included a large British force of about 1,400 soldiers and 2,500 carriers, led by Vice Admiral Harry Rawson arrived in 1897, this shameless group looted the African artifacts almost leaving the palaces with nothing other than destroyed infrastructures.

«A photograph captured by Félix Bonfils of a street vendor in Egypt selling mummies and other artifacts to tourists 1875» Paul Hudson, 2022.

Around 1875, selling of mummies and other artifacts to rich tourists was the order of the day, this was fueled by Victorian era fascination with ancient Egypt. The artifacts were always used for “ mummy unwrapping parties» as entertainment. Some times they were grounded into powder to create mummy brown the pigment which was used by the artists. This kind of trade involved a lot of exploitation but unfortunately there were no laws to protect these artifacts.

Amadou-Mathar M’Bow -1974. Paul Hudson, 2022.

Sarah V. B. (2022). Continues to articulate that in 1978, Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow, the Senegalese director of UNESCO, called upon the global public to consider restitution of cultural heritage removed during colonialism. He argued that being robbed of cultural objects, human remains, and art equaled the removal of collective memory and a sense of self. He called for the creation of bilateral agreements to enable the return of heritage, but also pointed out the responsibility of individual cultural institutions in the Global North to share collections. Ironically, it was the shortcomings of a UNESCO convention that brought M’Bow to this position. With the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, UNESCO attempted to address the issue of the loss of cultural heritage in formerly colonized countries.

Some of the famous African looted artifacts during the colonial period.

Chimbidzikai M. (2025) asserts that:

«…. Above all else, we need to acknowledge that returning artefacts to their rightful owners is not just about the politics of value. It is a process that is meant to rehumanize what had been classified as objects. True justice lies in granting these communities the autonomy to determine how their artifacts are preserved, interpreted, and engaged with globally. This self-determination is not merely a right. it is the foundation of healing.»

In the process of collection evaluation by the African Museums, one of the strategies taken was to demand for the looted Artifacts during the period of colonialism. The need to interpret and preserve the artifacts by the rightful owners triggered this movement which was spearheaded by some of the African lions like Amadou-Mathar M’Bow.

Section 3:

Collection assessment: A case study of Uganda Museum, Buganda Museum, Igongo Museum, Great Lakes Museum, Nairobi National Museum and Rwanda Museum.

Dosseman, Urfa City museum storage-2019 (On the left) Jean Housen, African Royal Museum-2019 (On the right)

Urfa City museum storage is situated in a large mansion (or maybe two) next to the Kara Musa mosque and close to the small stretch of city walls. It is of a type one often see: lots of items, gifted by locals and arranged along the lines of trades, crafts, or in reconstructed interiors from a not-too-distant past, and some showcases about the old history, with maybe some items like a mammoth’s tooth, or with some reconstructions shown on paintings on the walls (with Göbeklitepe nearby the reconstructions were spectacular). I hardly give captions as I think the pictures and their names explain themselves. (Dosseman, 2019).

«Part of the Uganda Museum ‘s building showing the entrance to the exhibition hall» Solomon, 2020.

Uganda National Museum (UGM) is Uganda’s national and the oldest museum in East Africa, established in 1908 at Lugard’s fort (currently Buganda Museum) on Old Kampala Hill in Kampala city. Its current building (Fig. 6) was established in 1954 and designed by the architect Ernst May. The collection grew from archaeological and paleontological excavations by scientists such as Edward Wayland, Bishop J. Wilson, and Church Hill among others from 1920 to 1940 (Pers. comm., see also: Rivard, 1984; Ogura, 2005; Demissie, 2012; Byerley, 2019). Objects recorded during the survey included home tools, cultural wears, and models of indigenous houses, musical instruments, a collection of Ugandan music, material from science and technology such as an old vintage car of Captain Lugard, and photographs depicting the history of the country. However, the museum also had a considerable collection of natural history specimens including round skins, and bones of mammals, birds and reptiles, as well as a geological and paleontological collection containing many fossils. The reptile wet collection is the oldest collection in Uganda. (Solomon. S, 2020)

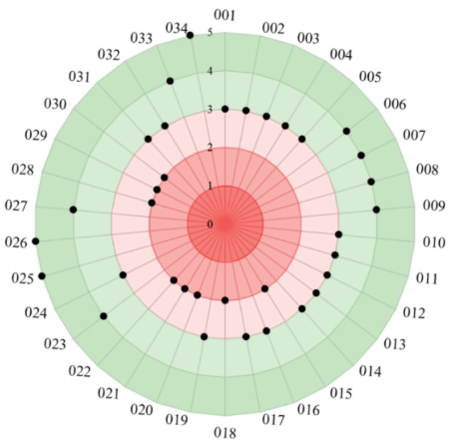

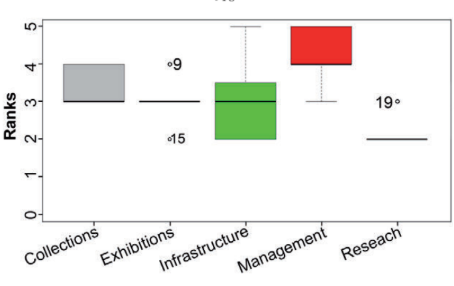

The detailed assessment for the Uganda museum. Solomon. S. (2020)

The pie-chat above shows a detailed assessment for the Uganda museum’s collections, exhibitions, management research and infrastructure. The author clearly explains the details as follows: Quality criteria: 1) very low quality, 2) low quality, 3) moderate quality, 4) high quality, 5) very high quality. The credit goes to Solomon Ssebuliba for this enormous evaluation. This assessment depicts how African museums are moving from being passive storages of colonial collections to becoming active agents in reinterpreting and reclaiming their cultural narratives. For detailed information about this assessment, you can follow the link attached on the list of image sources.

«Fort Lugard’s house turned into Buganda Museum. Behind the museum is the Old Kampala mosque» . (Solomon. 2020)

Some researchers asserts that Fort Lugard’s house became the Buganda Museum, while others disagree with this, but the amazing history about it, is that it was the original location for the Uganda Museum which was founded in 1908. When the museum’s collection grew, it was moved from Fort Lugard to Makerere University in 1941 and then to its current home on Kitante Hill in 1954.

«Igongo Museum» Solomon. 2020

In 2009, a museum named Igongo was established by entrepreneur James Tumusiime to preserve and promote the culture of southwestern Uganda. It was constructed on the former grounds of the Ankole Kingdom’s King Omugabe Kahaya II and opened in 2011 by President Museveni. It is a multifaceted institution featuring a cultural hamlet, a museum, and a reconstructed royal palace from the Mpororo Kingdom.

«Great Lakes Museum» Solomon. 2020

The «Great Lakes Museum» in Uganda was opened in 2014 with the main aim of preserving and showcasing the history and culture of the local tribes along the road connecting Ntungamo and Kabale. It displays artifacts from different tribes such as the Bakiga, Banyarwanda, Ankole and Baziba peoples, as well as modern relics like phones and cameras.

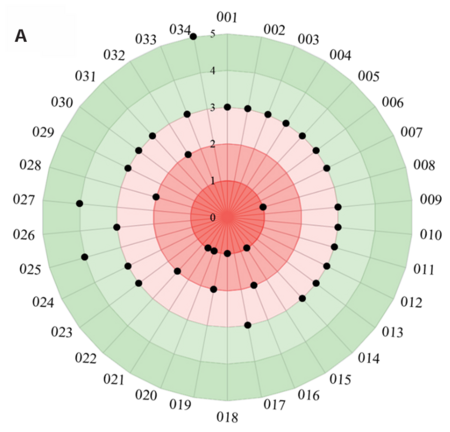

The pie-chats showing assessment for Buganda Museum (A) and Great Lakes Museum (B) and Igongo Museum, Sebuliba.2020

The pie-chats above shows a detailed assessment for Buganda Museum (A) and Great Lakes Museum (B) and Igongo Museum collections, exhibitions, management research and infrastructure. Despite the slight difference in Rankings, they all have a common goal of restoring and preserving the African collections.

Nairobi National Museum. Photo by Bountiful Safaris.2020

The history of Nairobi Museum goes back in 1910 when the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society founded a small museum in Nairobi. It was articulated that the museum moved to its current location on Museum Hill in 1930, where it was officially opened as the Coryndon Museum after former Kenya Governor Sir Robert Coryndon. After the Kenya’s independence in 1963, the Museum was renamed to Nairobi National Museum.

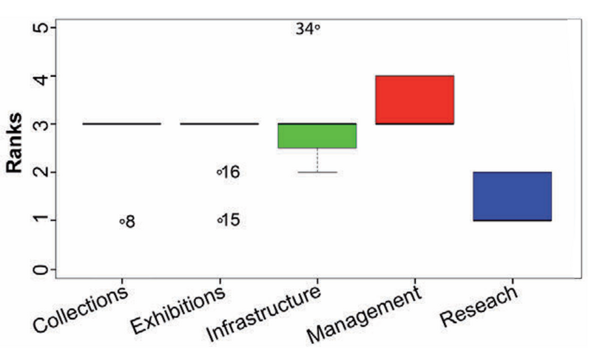

The pie-chat showing summary assessment for the Nairobi national museum.Sebuliba.2020

«Part of the building complex of the Institute of National Museums of Rwanda where the Ethnographic museum is also situated» Inkomoko, 2023.

The pie-chat showing assessment for the Ethnographic Museum of Rwanda (A) Sebuliba.2020

The national museum of Rwanda emerged from the Ethnographic Museum, which was gifted by Belgium in 1989, The museum, located in Butare, initially operated under the Institute of National Museums of Rwanda but was later merged into the Rwanda cultural Heritage in 2020. The main purpose of the museum is to preserve and showcase Rwandan cultural heritage, with extensive ethnographic and archaeological collections.

It should be noted that despite of the slight differences in collections assessment, exhibitions, infrastructure, management and research in African museums, they are all united with the main goal of preserving the African identity as well as restoring the lost African artifacts.

Section 4:

Some of the internationally recognized traditional and contemporary African artists who engage with themes of heritage and restitution.

Some of the outstanding artworks by African iconic Artists with themes of restitution, colonialism and heritage.

A portrait of Yinka Shonibare, Stephen Friedman Gallery. 2025

Yinka Shonibare is one of the great African artists famous for his vibrant and critically acclaimed works that explore themes of colonialism, race, and class, often using a signature material: the brightly colored Dutch wax print fabric. He is widely known for his large-scale sculptures, installations, and other works such as painting, and photography. His art reimagines historical scenes and art historical works, using headless figures draped in the patterned fabrics to comment on cultural identity and globalization.

El Anatsui’s portrait, Kindred Viewpoints, 2016.

El Anatsui is a renowned sculptor and artist from Ghana known for creating large-scale installations from recycled materials, especially aluminum bottle caps sewn together with copper wire. El Anatsui’s work explores themes of consumerism, waste, and post-colonial history. He transforms discarded materials into «metallic cloth-like» wall sculptures that can be reconfigured for different spaces.

Wang chi Mutu a Kenyan iconic contemporary artist, George Tubei, 2017.

Wangechi Mutu is a Kenyan-born contemporary artist internationally recognized for her provocative and visually rich works that explore issues of gender, race, colonialism, and identity. She is a very talented woman, and her multidisciplinary practice includes drawing, collage, sculpture, and performance.

A portrait of Dr. Lilian Mary Nabulime. Kampala Arts Trust & Afriart Gallery, 2020.

Dr. Lilian Mary Nabulime is a Ugandan iconic sculptor and senior lecturer of Fine Art. She is lecturing at College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology (CEDAT), Makerere University and has published and exhibited her works in various exhibitions both national and international. She works with everyday materials, such as wood, but also incorporates objects like metal parts, soap and mirrors.

«Lilian Nabulime carving wood into a wooden sculpture piece at her workshop in Kyanja» by Hajarah Nalwadda, 2023.

She is known for her large-scale, organic sculptures that often follow the natural grain and form of the wood. Her work is noted for its ability to transform ordinary materials into powerful statements. Her art is deeply socially conscious. Her PhD research focused on using sculptural forms as a communication tool for women living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda, a subject she approached with sensitivity and humor, using materials like soap and incorporating rotten seeds in male genitalia sculptures to symbolize risk. (Kampala Arts Trust & Afriart gallery. 2020)

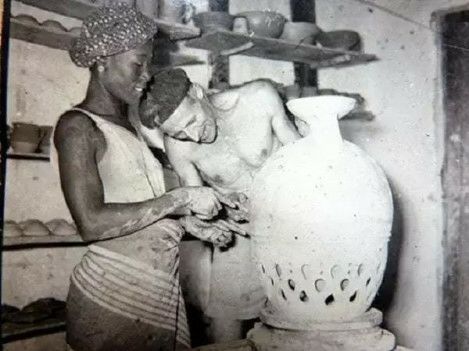

Ladi Kwali Renowned potter and ceramist; her legacy is a subject of discussion for better documentation and recognition. This Trend Administrator, 2024

Lady Kwali was born in the village of Kwali in 1925, the Gwari region of Northern Nigeria, where pottery was an indigenous female tradition. Her pots were noted for their beauty of form and decoration, and she was recognized regionally as a gifted and eminent potter. Several were acquired by the Emir of Abuja, Alhaji Suleiman Barau, in whose home they were seen by Michael Cardew in 1950.She learned to make pottery as a child by her aunt using the traditional method of coiling.

Ladi Kwali. Nigeria, 20 Naira banknote, 2017.

She is the only Nigerian woman to be featured on a currency note — 20 naira. She left an indelible legacy of her numerous works and a school of ‘students’ who inadvertently, picked up from where she stopped at the prestigious Abuja Pottery Training School center. She died on August 12, 1984.8. A sculpture of her is being made by Ambrose Diala. A road in Abuja has been named after her, named Ladi Kwali road. Wali was awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) in 1962.

The photo of Ladi Kwali in her workshop making ceramic pieces. This Trend Administrator, 2024

In 1977, she was awarded an honorary doctoral degree from Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria. Ladi Kwali’s pots were featured in international exhibitions of Abuja pottery in 1958, 1959, and 1962, organized by Cardew. In 1961, Kwali gave demonstrations at the Royal College, Farnham, and Wenford Bridge in Great Britain. She also gave demonstrations in France and Germany over this period. (This Trend Administrator, 2024)

The amazing point about these artists is that they use unique styles that depicts the true image of African art, especially the works that were looted during the colonial period. By doing this, their works indirectly fill the gap that was caused by the colonialists through recreating the character of the looted artifacts.

Section 5:

Technological applications in African museum settings

Use of virtual reality by African Museums

«FilmEU RIT project, Congo VR, launches the Panorama of Congo exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History and Science in Lisbon — IADT», 2025

Barry D. (2025) articulates that:

«Congratulations to everyone involved in the Congo VR project. This initiative stands out as a remarkable example of artistic research and a testament to the strength of interdisciplinary collaboration. By bringing together talents from across Film EU institutions, Congo VR has set a new benchmark in exploring historical narratives through virtual reality. It’s a significant achievement that demonstrates the incredible possibilities when researchers in film, technology, and academia join forces. Well done to the team for their dedication and for highlighting the importance of unity and innovation in pushing the boundaries of what we understand through art».

The use of Virtual reality in African museums depicts their readiness to independently preserve the African artifacts. Western countries should also be recognized for their support in the process, However, in the movement for decolonization of African museums, this does not stop the demand for retained African artifacts in Western Museums.

«LeAnn. K, adjusts a virtual reality headset worn by a Liberian student to engage in Liberian cultural objects currently housed within U.S. collections.» Craig S.& Chrislyn L, 2025.

Use of virtual reality by African museums is one of the strategies employed to make collections accessible and interactive. The African Museums have created applications that help in the restoration process of African Collections. They also went ahead to digitalize artifacts for virtual tours. The use of Virtual reality by African Museums has enabled users to remotely explore artifacts and sites.

Use of 3D scanning by the African Museums

«A photo of Wiiboox Reeyee Pro 3D scanner», Romala Govender, 2023(on the left) & 3D Artec Spider. Artec Europe, 2025 (on the right)

«Inside TBI’s research facility.» Artec Europe, 2025

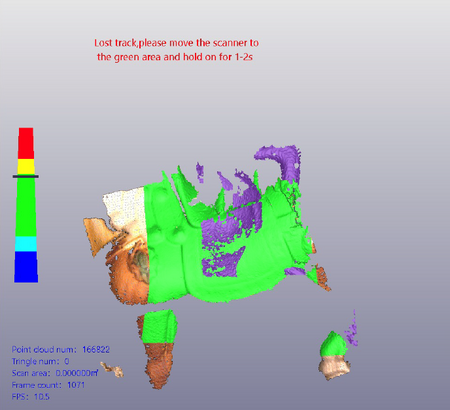

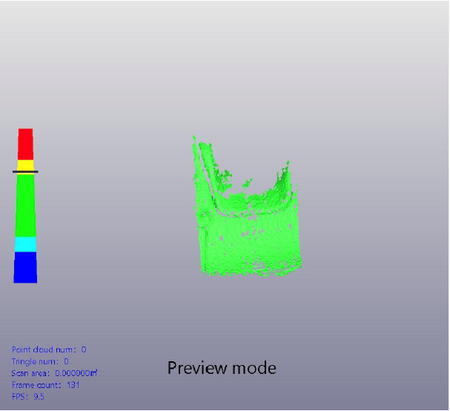

Image (on the left) shows a handheld scanning preview mode and Lost tracking during handheld scanning (image on the right), Romala Govender. 2023

«Opistophthalmus carinatus production process.» Anton du Plessis, Johan Els, Stephan le Roux, Muofhe Tshibalanganda, Toni Pretorius.2020

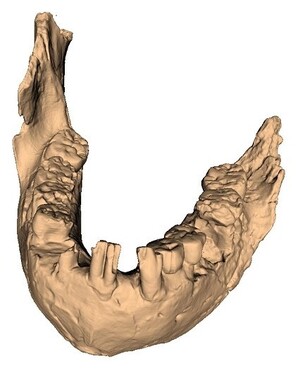

«A photo of 1.9-million-year-old skull of H. habilis that was 3D scanned with Artec Spider at hominid excavation sites in Kenya» Artec Europe, 2025

APET Secretariat, (2024) states that:

«…3D cultural preservation programs can establish dedicated initiatives for the scanning and documentation of cultural heritage sites, fostering collaboration between government agencies, universities, and private companies. These programs can also focus on skills development and training, equipping local communities with proficiency in 3D technology, including laser scanning and data processing, thereby creating job opportunities and empowering communities to preserve their heritage.»

APET, (2024) also continues to articulate that:

«…proposes that integrating 3D technology into cultural heritage tourism can enhance tourist attractions and generate revenue for local communities, while clear intellectual property frameworks ensure communities benefit economically from their heritage.»

APET, (2024) finally asserts that:

«…3D printing is transforming the approach to preserving Africa’s cultural heritage, offering solutions for safeguarding delicate artefacts, restoring damaged structures, and increasing accessibility to cultural treasures».

Scanning of African artifacts as one of the evaluation strategies is a great innovation, the process is surrounded by numerous opportunities which includes making of these artifacts accessed online, preservation as well as creating employment opportunities to various institutions, manufacturing companies such as Artec and people who works in the scanning projects.

«Dennis and Steve put the final touches on a 3D-printed belt from the Kamba community in Kenya as part of a collaboration to produce replicas of artifacts kept in German museums». Brian Otieno, 2022.

In the process of evaluation of collections, African museums introduced the use of 3D scanning and printing in order to digitally preserve cultural heritage and provide a global access to artifacts. Projects and initiatives such as Zamani and MILELE contemporary Lab have fought tooth and nail to preserve and promote African cultural practices. Several Museums like Iziko Museums of cape Town, National Museum of African Art, National Museum in Bloemfontein and University of Pretoria Museum employs use of 3D scanning for research and documentations of their collections.

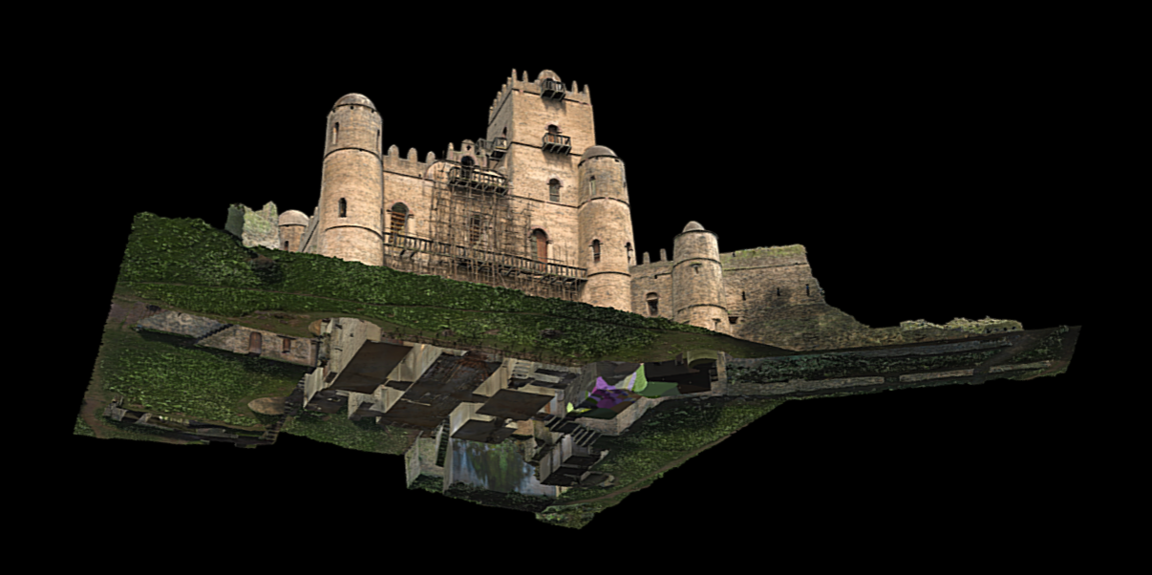

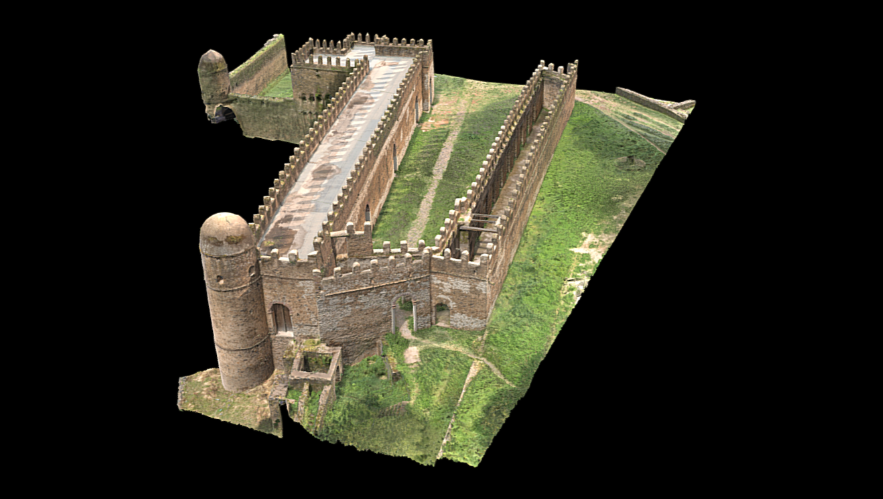

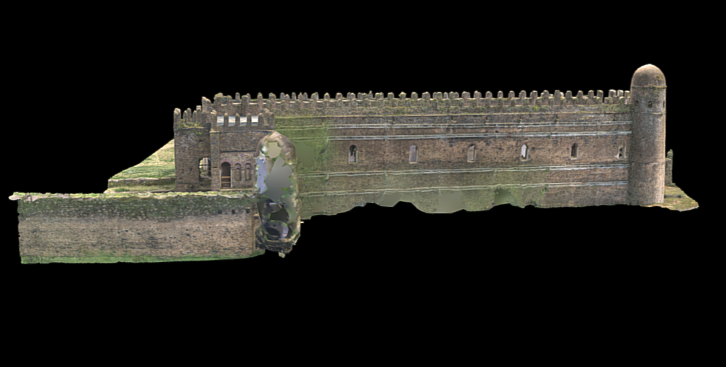

3d model scans of emperor fasilides' castle Gondar, Ethiopia (Zamani Project)

The 3D model scan of Bakafa’s Castle, Ethiopia by Zamani Project

Use of interactive gaming by African Museums

The game «Relooted» about the return of African artifacts from Western museums developed by Nyamakop, Sam Peters, 2025.

«Relooted is set in a futuristic Johannesburg», Sam Peters, 2025.

«Among the artifacts to be „Relooted“ is a Yehoti Mask — made by the Bwa people of Burkina Faso», Sam Peters, 2025.

The game titled «Relooted» was developed by the South African studio Nyamakop that centers on the repatriation of African artifacts from Western museums. In this game, the players use a crew of scientists and MMA fighters, led by a retired art historian, to recover 70 real-life artifacts, such as the Benin Bronzes, which were often taken during colonial rule. The main aim of this game is to educate players about the history and cultural significance of these artifacts taken by the colonialists through its gameplay.

Section 6: Conclusion

This visual research into the evaluation of collections by African museums has moved beyond a simple audit of objects to a critical examination of power, memory, and identity. It is not a mere assessment of artifacts but an act of rewriting African history, reclaiming cultural sovereignty, and maintaining African identity. The process is not a single solid event; it involves embracing digital tools for broader access, correcting historical injustices through restitution, and fundamentally shifting institutional purpose to serve contemporary African societies. By employing a visual methodology, analyzing not just what is collected but how it is stored, displayed, and contextualized, this study has illuminated the complex and often contentious space that museum collections occupy in the contemporary African context. The colonial legacy remains a visible and often un-sutured wound within the storage rooms and galleries of African museums; a profound paradigm shift is underway, moving from a preservation-centric model to a relevance-driven one; and the very process of evaluation, when made visible, becomes a powerful tool for restitution, reconciliation, and reclamation.

Section 7:

List of Image Sources and Bibliography

Ambrose T. & C. Paine, (2018): Museum Basics: The International Handbook: — 4th ed. London, Routledge: 508 pp.

Benedicte. S, (2022): Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat. Princeton University Press,

Sarah. B, (2015): Authentically African. Arts and the Transnational Politics of Congolese Culture. Ohio University Press.

Dan. H, (2020): The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Cultural Violence, and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press.

Jos V. B, (2017): Treasures in Trusted Hands. Negotiating the Future of Colonial Cultural Objects. Sidestone Press.

«The role of sculptural forms as a communication tool in relation to the lives and experiences of women with HIV/AIDS in Uganda». Archived from the original on 07.03.2016. Retrieved 28.04.2018.

Soni. D, (1997): The British and the Benin Bronzes. ARM Information Sheet 4, Campaign for the Return of the Benin Bronzes, 1997. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

Igbafe, Philip A. (1970): «The fall of Benin: A Reassessment». Journal of African History. XI (3): 385–400. doi: 10.1017/S0021853700010215. JSTOR 180345. S2CID 154621156.

6.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344489585- 15.11.2025.

8.https://rw.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dosiye:Rwanda_Mesium.jpg -16.11.2025.

10.https://www.behance.net/gallery/85241583/Wangechi-Mutu-Collage -17.11.2025.

ng/15.03.2017-facts-about-ladi-kwali-pottery-woman.html -19.11.2025.

13.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Mary_Nabulime -19.11.2025.

https://kampalabiennale.org/lilian-nabulime/ -20.11.2025.

15.https://www.duendeartprojects.com/artworks/71-lilian-mary-nabulime-keeping-safe-from-covid-19-2020/ -20.11.2025.

https://iadt.ie/news/panorama-of-congo/ -22.11.2025.

https://ispr.info/2025/04/29/traveling-treasures-how-virtual-reality-is-restoring-liberias-culture/ -23.11.2025.

https://www.artec3d.com/cases/kenya-expedition-1 -23.11.2025.

https://edition.cnn.com/world/africa/relooted-video-game-african-artifacts-western-museums-spc -23.11.2025.

https://elanatsui.art/biography -23.11.2025.